Highly religious people are distinctive in their day-to-day behaviors in several key ways: They are more engaged with their families, more involved in their communities and more likely to report being happy with the way things are going in their lives.

In other ways, however, there is little discernible difference in the way highly religious people and those who are less religious live their everyday lives. There is little indication, for instance, that highly religious people are more attentive to their health (e.g., by eating right and exercising regularly) or more socially conscious about the environment or about trying to buy products from companies that pay employees a fair wage. And in their interpersonal interactions, highly religious people are no less likely than others to lose their temper and only slightly less likely to tell a white lie.

The remainder of this chapter explores these topics in more detail. It also includes an assessment of how Americans relate to God on a day-to-day basis (e.g., by thanking God, asking God for guidance or help, or becoming angry with God).

The chapter reports data on these behaviors for Americans overall – sorted by those who are highly religious and those who are not – and for a variety of religious groups (including adherents who are highly religious and less so). For differences within particular religious groups by level of religiosity, see the detailed tables.

Highly religious people more likely to attend family gatherings, express satisfaction with family life

Highly religious Americans – those who pray every day and attend religious services at least once a week – gather more often with their extended families than less religious Americans do. About half of those who are highly religious (47%) say they attend a gathering with extended family at least once or twice a month, compared with 30% of those who are less religious. At the same time, those who are not highly religious (by the definition used in the report) are roughly twice as likely as those who are highly religious to say they “seldom” or “never” gather with their extended families; 31% of less religious people say this, compared with 16% of those who are highly religious.

These differences persist even after taking into account factors such as marital status and presence of minor children in the home.

There could be many reasons for the association between religion and family gatherings. In some cases, the links may be clear and direct, such as when extended families gather for religious holidays or religious occasions such as baptisms or confirmations. But there also may be links that are less obvious, such as the possibility that people who enjoy getting together with relatives are generally outgoing and sociable, and therefore perhaps also more likely to enjoy going to religious services.

The survey also looks at differences among religious groups.9 It finds that Catholics (42%), Jews (38%) and Protestants (36%) all are more likely to say they gather at least once or twice a month with extended family than are religiously unaffiliated Americans (24%). And, conversely, religious “nones” are more likely than religiously affiliated Americans, as a whole, to say they seldom or never attend extended family gatherings (37% vs. 24%). These differences between religious groups are apparent even after controlling for other factors – such as age, education, race and gender – that also may be correlated with gathering with extended family.

Roughly three-quarters of those who are highly religious (74%) say they are “very satisfied” with their family life, compared with two-thirds of those who are less religious (67%).

Looking at the data by religious group, the survey finds Christians are modestly more likely than those from non-Christian faiths and the religiously unaffiliated to say they are very satisfied with their family life (70% vs. 64% and 65%, respectively). Members of churches in the historically black Protestant tradition are somewhat less satisfied with their family life compared with people in other Christian traditions.

These patterns partly reflect socioeconomic factors; adults who are married are more likely than unmarried adults to say they are very satisfied with their family life (80% vs 59%), and high-income earners are more likely than lower-income earners to say they are very satisfied with their family life. Members of churches in the historically black Protestant tradition are less likely than other Christians to be married or to report high incomes.10 However, even after controlling for differences such as income and marital status, Christians remain more satisfied with their family lives than those who are religiously unaffiliated.

When commenting on life more generally, Americans who are highly religious are more likely than those who are less religious to report being very happy in their lives (40% vs. 29%).11

Differences among people from various religious traditions are modest on this question. One-third of Protestants say they are “very happy,” as do 35% of Catholics and 29% of those who identify with non-Christian faiths or with no religion. Within Christian groups, those who are highly religious express more happiness with the way things are going in their lives than do those who are less religious. (See detailed tables.)

Religion more frequent topic of conversation among highly religious Americans

Highly religious people are much more likely than those who are less religious to discuss religion regularly – both with family members and with people outside their family.

Evangelical Protestants and members of historically black Protestant churches are more likely to talk about religion on a regular basis than are people from other religious traditions. And religious “nones” are far less likely than those who identify with a faith to say they discuss religion with any regularity.

When someone disagrees with them about religion, most Americans say the best thing to do is to try to understand the other person’s point of view and agree to disagree. But about one-in-four (27%) say the best thing to do is avoid discussing religion with those who disagree with them. A scant 5% say the best course is to try to persuade the other person to change his or her mind.

Adults who are highly religious themselves are somewhat more inclined to say the ideal approach when discussing religion is to try to persuade the other person of the correctness of one’s own point of view. And those who are less religious are about twice as likely as highly religious Americans to say the best course is to avoid discussing religion altogether (31% vs. 15%). Still, large majorities in both groups say the best approach is to agree to disagree.

Volunteering most common among highly religious

Adults who are highly religious are more likely than those who are less religious to say they did volunteer work in the last seven days (45% vs. 28%). Follow-up questions suggest this difference is driven primarily by volunteering through houses of worship.12 Highly religious Americans are more than five times as likely as those who are less religious to say they recently volunteered “mainly through a church or other religious organization” (23% vs. 4%). Similar shares of highly religious and less religious adults say they volunteered through an institution other than a church or house of worship.

About two-thirds of highly religious adults say they donated time, money or goods to help the poor in the past week (65%). Fewer of those who are not highly religious say the same (41%). Christians and Jews are more likely than religious “nones” to say they donated money, goods or time to help the poor and needy in the given time frame. These differences between Christians and Jews on the one hand and religious “nones” on the other persist even after taking into account other potential explanatory variables, such as income, age and education.

Highly religious no more likely than less religious to keep their cool

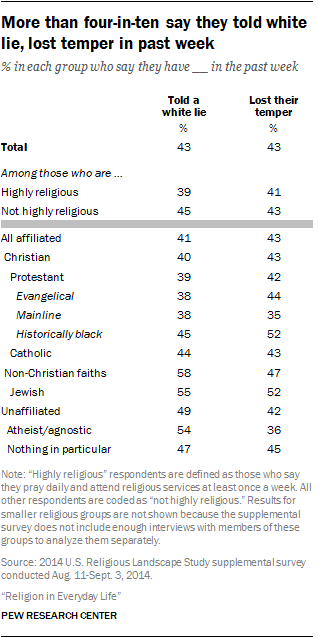

There is only a modest difference between those who are highly religious and those who are not in terms of the shares who say they have told a white lie recently, and no significant difference in the shares who have lost their temper. About four-in-ten highly religious adults (39%) and 45% of those who are not highly religious say they told a white lie in the past week. And 41% of highly religious people say they lost their temper recently, as did 43% of those who are not highly religious.

About six-in-ten adults who belong to a non-Christian faith (58%) and 49% of religious “nones” say they told a white lie in the past week. Among Christians, 40% say they fibbed recently. Christians and religious “nones” are about equally likely to say they lost their temper in the past week.

Little connection between religion and living a healthy lifestyle

Religion has only a small impact on the way Americans perceive their health, according to the survey. About half or more of those who are highly religious (54%) and those who are not (51%) say they are “very satisfied” with their health. Similar shares of Christians (51%), members of non-Christian faiths (51%) and the religiously unaffiliated (53%) say they are very satisfied with their health.13

Similarly, there is virtually no difference in the self-reported frequency of exercise between adults who are highly religious and those who are not. About three-in-ten in each group say they did not exercise in the past week, while roughly half in each group say they exercised somewhere between one and four times. Among both highly religious and less religious adults, about one-in-five report exercising five times or more within the past seven days.

There is little variability across religious traditions regarding exercise frequency.

Highly religious people are more inclined than those who are less religious to meditate as a coping mechanism for stress (42% vs. 26%). The survey also shows that Christians, especially those in the historically black Protestant tradition, are more likely than Jews and religious “nones” to turn to meditation to cope with stress.

There is little connection between religion and reported levels of overeating. Nearly six-in-ten highly religious adults (58%) say they overate recently, identical to the share of less religious adults who say the same. Similarly, there are few differences on this question among respondents from various religious traditions.

Highly religious Americans no more likely to recycle or to consider the environment in purchasing decisions

There are virtually no differences in self-reported recycling practices between those who are highly religious and those who are not. Among both the highly religious and less religious, roughly three-quarters say they recycle either “whenever possible” or “most of the time.” About one-in-five say they recycle only “occasionally,” and just 4% say they “never” make such efforts.

Non-Christians are slightly more likely than Christians to say they do as much as they can to recycle and reduce waste; 51% of non-Christians say they recycle and reduce waste whenever possible, compared with 44% of Christians. This difference remains even after controlling for such factors as age, income and education.

There is very little connection between religion and the way Americans say they make purchasing decisions. Highly religious adults are no more likely than those who are less religious to say they consider a company’s environmental record or its treatment of its employees when making purchasing decisions. And people from all religious backgrounds prioritize quality and price over environmental concerns and employee wages when deciding what products to buy.

Virtually all highly religious people regularly express gratitude to God and ask for help, as do majorities of less religious people

Virtually all adults in the survey who are highly religious say they have thanked God for something (99%) and asked God for help (98%) in the past week. By contrast, roughly two-thirds of those who are less religious say they thanked God for something (68%) in the past seven days, and just over half (55%) say they asked God for guidance.

Far fewer Americans say they got angry with God in the past week. There is only a slight difference on this question between those who are highly religious and those who are not.

About eight-in-ten or more members of all Christian groups say they thanked God for something over the course of the previous week, including 96% of those belonging to historically black Protestant churches and 93% of evangelical Protestants. Members of non-Christian faiths and those who identify as religiously unaffiliated are significantly less likely to express gratitude to God in their day-to-day lives, but substantial shares still say they gave thanks in the past week (63% and 37%, respectively). (For data on belief in God among different religious groups, see the Religious Landscape Study.)

When it comes to asking God for help or guidance, members of historically black Protestant churches (91%) and evangelicals (87%) again stand out from other Christian traditions. By comparison, about half of members of non-Christian faiths (51%) and a quarter of religious “nones” (25%) report asking God for help in the past seven days.