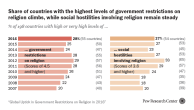

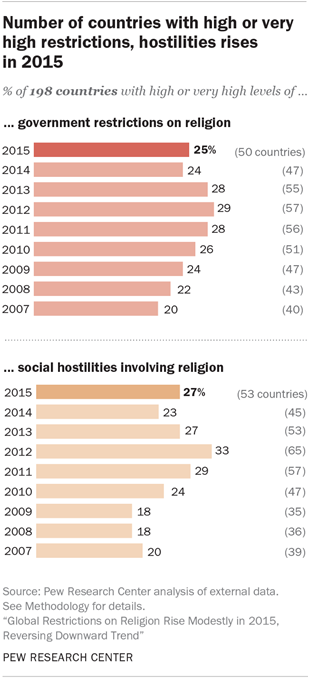

Government restrictions on religion and social hostilities involving religion increased in 2015 for the first time in three years, according to Pew Research Center’s latest annual study on global restrictions on religion.

The share of countries with “high” or “very high” levels of government restrictions – i.e., laws, policies and actions that restrict religious beliefs and practices – ticked up from 24% in 2014 to 25% in 2015. Meanwhile, the percentage of countries with high or very high levels of social hostilities – i.e., acts of religious hostility by private individuals, organizations or groups in society – increased in 2015, from 23% to 27%. Both of these increases follow two years of declines in the percentage of countries with high levels of restrictions on religion by these measures.

When looking at overall levels of restrictions in 2015 – whether resulting from government policies and actions or from hostile acts by private individuals, organizations or social groups – the new study finds that 40% of countries had high or very high levels of restrictions, up from 34% in 2014.

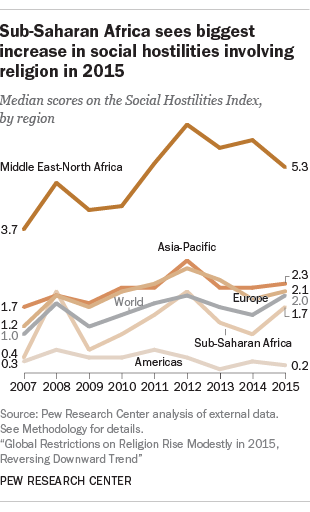

In addition to a rise in the percentage of countries with high or very high levels of government restrictions and social hostilities involving religion, religious restrictions also rose in 2015 by other measures. For example, more countries saw their scores on the Government Restrictions Index (based on 20 indicators of government restrictions on religion) increase rather than decrease (see Chapter 1). And the global median score on the Social Hostilities Index, based on 13 measures of social hostilities involving religion, ticked up in 2015 (see Chapter 3).

The global rise in social hostilities reflected a number of factors, including increases in mob violence related to religion, individuals being assaulted or displaced due to their faith, and incidents where violence was used to enforce religious norms. In Europe, for instance, there were 17 countries where incidents of religion-related mob violence were reported in 2015, up from nine the previous year. And sub-Saharan Africa saw a spread in violence used to enforce religious norms, such as the targeting of people with albinism for rituals by witch doctors. This type of hostility was reported in 25 countries in sub-Saharan Africa in 2015, up from nine countries in 2014. (For more on rising religious restrictions in sub-Saharan Africa, see sidebar in Chapter 3.)

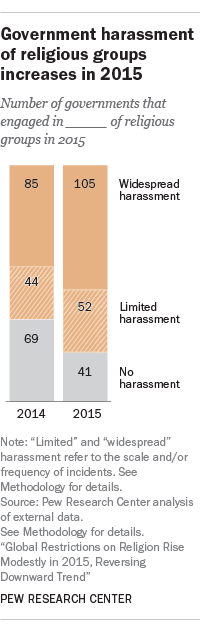

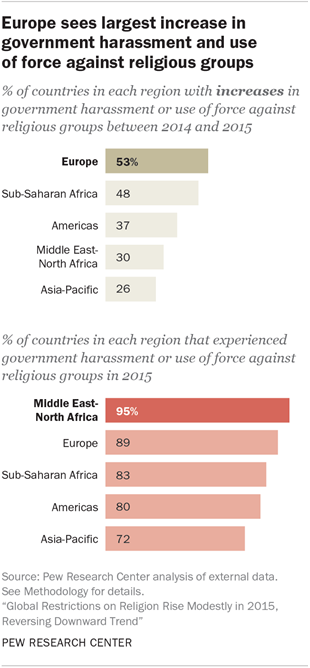

The increase in government restrictions was linked to a surge in government harassment and use of force against religious groups, two of the specific indicators used to measure government restrictions on religion in the analysis.1 Four of the five geographic regions analyzed in this report – the Middle East and North Africa, Asia and the Pacific, sub-Saharan Africa and Europe – saw increases in these two areas.

Of the 198 countries in the study, 105 (53%) experienced widespread government harassment of religious groups, up from 85 (43%) in 2014 and 96 (48%) in 2013. Limited harassment – cases that were isolated or affected a small number of groups – also rose, taking place in 52 countries (26%) in 2015 (up from 44, or 22% of countries, in 2014).

Government use of force against religious groups increased as well, with 23 countries (12%) experiencing more than 200 cases of government force in 2015, up from 21 (11%) in 2014. There was an even bigger increase in the number of countries with at least one, but no more than 200 incidents of government use of force against religious groups: 83 nations (42%) fell into this category in 2015, an increase from 60 countries (30%) in 2014.

Government harassment and use of force rising in Europe, along with social hostilities against Muslims

While the Middle East-North Africa region continued to have the largest proportion of governments that engaged in harassment and use of force against religious groups (95%), Europe had the largest increase in these measures in 2015. More than half of the 45 countries in the region (53%) experienced an increase in government harassment or use of force from 2014 to 2015. Twenty-seven European countries (60%) saw widespread government harassment or intimidation of religious groups in 2015, up from 17 countries in 2014. And the governments of 24 countries in Europe (53%) used some type of force against religious groups, an increase from 15 (33%) in 2014.

Two countries in Europe, France and Russia, each had more than 200 cases of government force against religious groups – mostly cases of individuals being punished for violating the ban on face coverings in public spaces and government buildings in France, and groups being prosecuted in Russia for publicly exercising their religion.2 France and Russia also were the only two European countries with more than 200 cases of government force against religious groups in 2014, but there was a significant rise in 2015 in the number of countries in Europe where lower numbers of incidents – between one and nine – occurred (eight in 2014 vs. 17 in 2015).

Some incidents of government harassment measured by this study – which are not always physical, but may include derogatory statements by public officials or discrimination against certain religious groups – were related to Europe’s incoming refugee population. In 2015, 1.3 million migrants applied for asylum in Europe, nearly doubling the previous annual high of about 700,000 in 1992, following the collapse of the Soviet Union. More than half (54%) came from three Muslim-majority countries – Syria, Afghanistan and Iraq.

One such example involved Hungary’s prime minister, Viktor Orban, who complained about the religious makeup of refugees coming into the country. In September 2015, he wrote in a German newspaper, “Those arriving have been raised in another religion, and represent a radically different culture. Most of them are not Christians, but Muslims.” He later told journalists, “I think we have a right to decide that we do not want a large number of Muslim people in our country,” and in another interview said “the Islamic religion and culture do not blend with Christian religion and culture; it is a different way of life.”3

Similarly, neighboring Slovakia rejected European Union mandatory refugee quotas, but said it would accept 200 Christian refugees from Syria. In August 2015, the Ministry of Interior explained the decision, saying Christian refugees would be better able to assimilate into Slovakian society than Muslim refugees given the lack of officially recognized mosques in the country. Earlier in the year, the leader of the Slovak National Party, Andrej Danko, had proposed a new law that would make it impossible to build Islamic religious buildings in the country.4

In addition to harassment by government officials, many European governments employed force against religious groups. For example, in February of 2015, German police raided the mosque of the Islamic Cultural Center in Bremen; the police said they suspected that the mosque supported Salafist groups and that a person associated with the mosque was distributing automatic weapons for a terror attack. Police broke down the front door of the mosque, handcuffed worshippers and forced some to lie on the floor for hours. No weapons were found in the mosque. In July, a Bremen regional court ruled that the search was unlawful.5

These incidents took place in a climate influenced by threats and attacks from religiously inspired terrorist groups. France experienced several religion-related terror attacks in 2015, including the Jan. 7 shooting at the offices of the satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo and the Nov. 13 attacks claimed by the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS) at the Bataclan concert hall and various other locations throughout Paris.6 In the days following the Paris attacks, Germany cancelled an international soccer match because of security threats, and Belgian authorities arrested 16 people suspected of planning similar acts.7

Altogether, European law enforcement officials reported record numbers of terrorist attacks either carried out or prevented by authorities in 2015, although not all of these events were directly related to religion.8

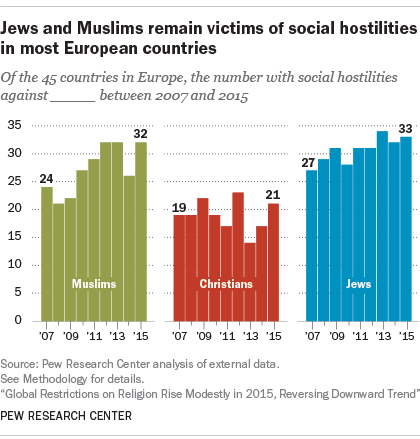

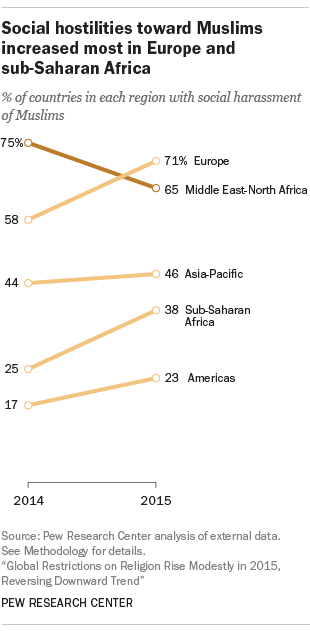

Attacks that were influenced by religion, such as those in Paris, are counted in the study as social hostilities involving religion – i.e., hostile actions motivated by religion and carried out by individuals or social groups, separate from government actions. In Europe, hostilities toward Muslims in particular increased considerably. In 2015, 32 countries in Europe (71%) experienced social hostilities toward Muslims, up from 26 countries (58%) in 2014. By comparison, social hostilities toward Christians spread from 17 (38%) countries in 2014 to 21 (47%) in 2015. Hostilities against Jews in Europe remained common and increased slightly, from 32 (71%) countries in 2014 to 33 (73%) countries in 2015. Many of the incidents targeting these religious groups occurred in the form of mob violence.

In the wake of the Charlie Hebdo and Bataclan concert hall shootings, some Muslims in France faced violent attacks by social groups or individuals. For example, two Muslim places of worship in the cities of Le Mans and Narbonne were attacked by grenades and gunshots the day after the Charlie Hebdo shooting. France’s Interior Ministry reported that anti-Muslim incidents more than tripled in 2015, including cases of hate speech, vandalism and violence against individuals.9

Vandals in Spain also targeted mosques after the Charlie Hebdo shooting in January of 2015.10 Perpetrators drew swastikas and threats on Spanish mosques and Islamic centers on four separate occasions that month.

In Slovakia, far-right political groups organized protests against the “Islamization of Europe and Slovakia,” drawing an estimated 3,000-5,000 people in Bratislava in June. The protest was called “STOP to the Islamization of Europe! Together against the Brussels dictate, for a Europe for Europeans.” Groups held two more protests in September and October along a similar theme.11

About this report

This is the eighth in a series of reports by Pew Research Center analyzing the extent to which governments and societies around the world impinge on religious beliefs and practices. The studies are part of the Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures project, which analyzes religious change and its impact on societies around the world. The project is jointly funded by The Pew Charitable Trusts and the John Templeton Foundation.

To measure global restrictions on religion in 2015 – the most recent year for which data are available – the study ranks 198 countries and territories by their levels of government restrictions on religion and social hostilities involving religion. The new study is based on the same 10-point indexes used in the previous studies.

- The Government Restrictions Index measures government laws, policies and actions that restrict religious beliefs and practices. The GRI is comprised of 20 measures of restrictions, including efforts by government to ban particular faiths, prohibit conversion, limit preaching or give preferential treatment to one or more religious groups.

- The Social Hostilities Index measures acts of religious hostility by private individuals, organizations or groups in society. This includes religion-related armed conflict or terrorism, mob or sectarian violence, harassment over attire for religious reasons or other religion-related intimidation or abuse. The SHI includes 13 measures of social hostilities.

To track these indicators of government restrictions and social hostilities, researchers combed through more than a dozen publicly available, widely cited sources of information, including the U.S. State Department’s annual reports on international religious freedom and annual reports from the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom, as well as reports from a variety of European and U.N. bodies and several independent, nongovernmental organizations. (See Methodology for more details on sources used in the study.)

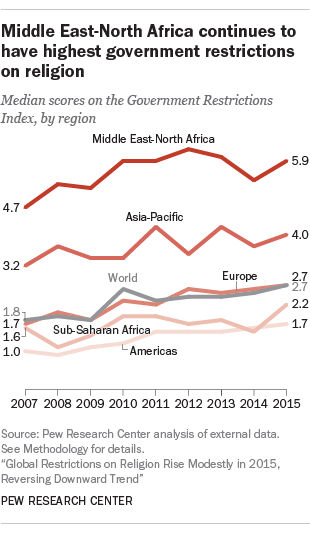

The new study also examines religious restrictions by region. The sharpest increase in median Government Restrictions Index score in 2015 occurred in sub-Saharan Africa, rising to 2.2 from 1.5 in 2014 (see sidebar in Chapter 3 for more information on changes in sub-Saharan Africa).12 But when looking at long-term trends, it is clear that a few other regions, including the Asia-Pacific region and Europe, have seen greater increases in median levels of government restrictions on religion since 2007. Indeed, the Middle East-North Africa region has seen the largest increase in government restrictions since 2007 and continued to have the highest level of these restrictions in 2015, with the region’s median score increasing to 5.9 from 5.4 in 2014.

Europe was one of the two regions where social hostilities toward religion rose in 2015, but sub-Saharan Africa experienced the largest increase in its median score during the year. The Middle East-North Africa region continued to have the highest levels of hostilities, despite a decline in 2015.

Combining government restrictions and social hostilities, four-in-ten of the countries included in the study are in the most restrictive categories (high or very high). But some of these countries are among the world’s most populous (such as Indonesia and Pakistan). As a result, 79% of the world’s population lived in countries with high or very high levels of restrictions and/or hostilities in 2015 (up from 74% in 2014). It is important to note, however, that these restrictions and hostilities do not necessarily affect the religious groups and citizens of these countries equally, as certain groups or individuals may be targeted more frequently by these policies and actions than others.

Among the world’s 25 most populous countries, Russia, Egypt, India, Pakistan and Nigeria had the highest overall levels of government restrictions and social hostilities involving religion. Egypt had the highest levels of government restrictions in 2015, while Nigeria had the highest levels of social hostilities.

Muslims and Christians – who together make up more than half of the global population – continued to be harassed in the highest number of countries. The study also finds that the number of countries where Jews were harassed fell slightly in 2015, after years of steady increases.