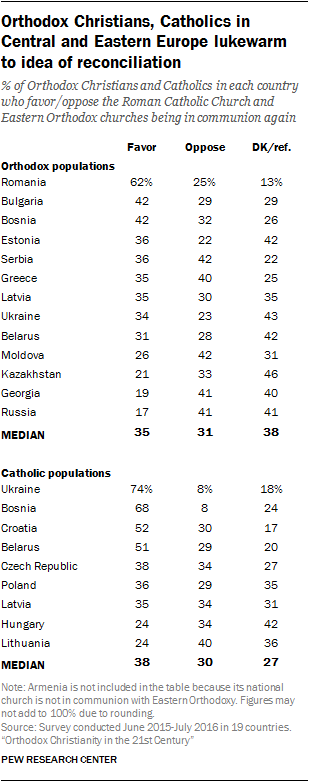

A host of disputes – ranging from theological to political – have divided Orthodoxy from Catholicism for nearly 1,000 years. But while some leaders on both sides have tried to resolve them, fewer than four-in-ten Orthodox Christians in the vast majority of countries surveyed say they favor their church reconciling with the Roman Catholic Church.

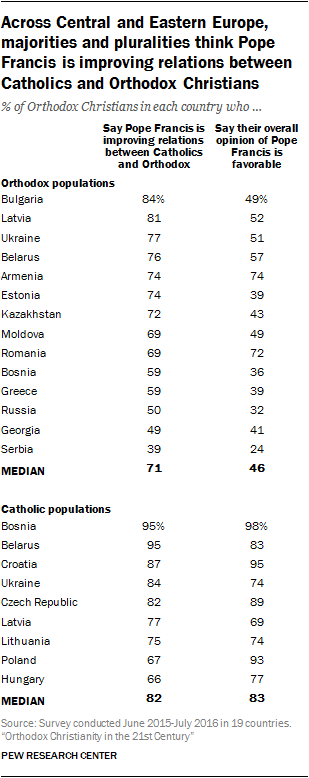

At the same time, Orthodox majorities in most countries say their religion and Catholicism have a lot in common, and Orthodox majorities across most of Central and Eastern Europe say Pope Francis has helped improve Orthodox-Catholic relations. Regarding Pope Francis in general, however, Orthodox opinion is mixed; half or fewer of Orthodox respondents in most countries surveyed say they view him favorably, including just 32% in Russia.

On two of the issues where Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic teachings diverge – whether to allow married clergy and whether to permit divorce – most Orthodox Christians favor their official church stances permitting divorce and allowing married men to be ordained as priests. Orthodox Christians also tend to support their church’s stances barring same-sex marriage and prohibiting the ordination of women as priests, issues on which their church aligns with Catholic positions. On balance, Orthodox women are as likely as men to oppose the ordination of women to the priesthood.

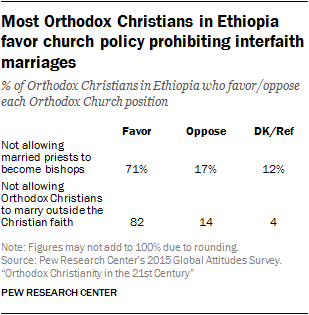

Orthodox Christians in Ethiopia were asked two additional questions. The results show that most respondents favor church policies that prevent married men from becoming bishops and forbid the Orthodox Church from marrying couples unless both spouses are Christian.

Orthodox Christians ambivalent about communion with Roman Catholic Church

Neither Orthodox Christians nor Catholics widely favor communion between their two churches, which have been in an official state of schism since the year 1054. In 12 of the 13 Central and Eastern European countries surveyed with sizable Eastern Orthodox populations, fewer than half of Orthodox Christians say they favor the Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic churches being in communion again. Only in Romania do a majority (62%) of Orthodox Christians support reunification, and only in Ukraine (74%) and Bosnia (68%) do most Catholics take this position. In many of these countries, about a third or more of Orthodox and Catholic respondents say they don’t know or can’t answer the question, perhaps reflecting a lack of understanding of the historical split.

In Russia, which has the largest Orthodox population in the world, just 17% of Orthodox Christians support communion with Catholicism.

Overall, Orthodox Christians and Catholics in Central and Eastern Europe offer similar responses to this question. But in the countries surveyed with sizable Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic populations, Orthodox Christians are often much less likely than their Catholic compatriots to support communion between the two churches. For example, in Bosnia, 42% of Orthodox Christians favor communion, compared with 68% of Catholics. Significant gaps also exist in Ukraine (34% of Orthodox vs. 74% of Catholics) and Belarus (31% vs. 51%).

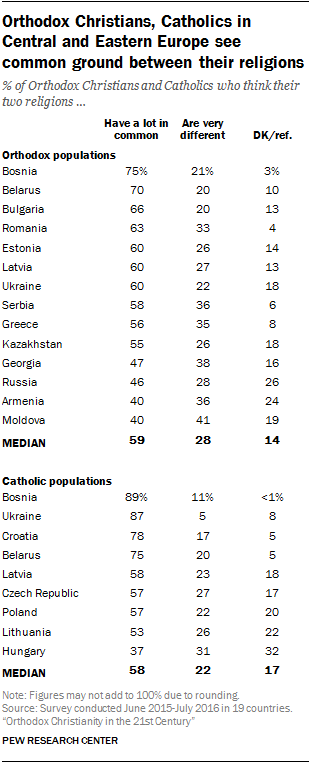

Orthodox, Catholics about equally likely to view their religions as similar

While relatively few favor a hypothetical communion between their churches, Orthodox Christians and Catholics generally say their religions have a lot in common. Majorities in 10 of the 14 Orthodox populations surveyed say this, as do majorities in seven of the nine Catholic populations.

Proximity to people of the other faith often seems to be a factor; respondents from these two traditions are especially likely to say their denominations have a lot in common if they live in countries with sizable populations of both. In Bosnia, for example, 75% of Orthodox Christians and 89% of Catholics say their religions have a lot in common. In Belarus, 70% of Orthodox Christians say this, as do 75% of Catholics.

Ukrainian Catholics are among the most likely in the region to say Catholicism has a lot in common with Orthodox Christianity. In part, this may be because most Ukrainian Catholics identify as Byzantine Rite Catholics and not Roman Catholics.

Many Orthodox say Pope Francis is helping Catholic-Orthodox relations, but fewer view him favorably

In 1965, Patriarch Athenagoras of Constantinople and Pope Paul VI agreed to rescind the mutual excommunications issued by their churches 911 years prior, in 1054. And today, majorities of Orthodox Christians in most countries surveyed say they believe Pope Francis – who has issued joint declarations with both Patriarch Bartholomew of Constantinople and Patriarch Kirill of Moscow – has been improving relations between Catholicism and Orthodoxy.

More than two-thirds of Orthodox Christians in Bulgaria, Ukraine and several other countries say Pope Francis has been improving relations. In Russia, however, only half take this view.

Much lower Orthodox shares report positive opinions of Pope Francis in general. Across the region, a median of just under half (46%) of Orthodox Christians view Francis favorably, including about a third (32%) in Russia. That is not to say that all others view him unfavorably; a median of just 9% of Orthodox Christians across these countries take this position, while a median of 45% say they have not formed an opinion or otherwise decline to answer.

Catholics, meanwhile, are largely united in their approval of the pope. Majorities of all nine Catholic populations surveyed also say Pope Francis has been improving their church’s relationship with Orthodoxy.

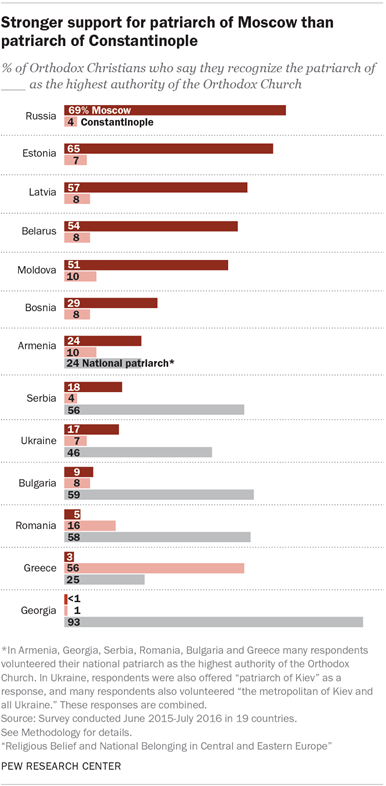

Orthodox more likely to view Moscow patriarch as highest religious authority than ecumenical patriarch of Constantinople

Orthodox Christians are more likely to invest religious authority in the patriarch of Moscow than in the ecumenical patriarch of Constantinople, even though the latter is traditionally known as the “first among equals” among Eastern Orthodox leaders.18

In every Orthodox-majority country surveyed that lacks a self-governing national Orthodox church, Orthodox Christians are much more likely to say they recognize the patriarch of Moscow (currently Kirill) as the highest authority in Orthodoxy than to say this about the patriarch of Constantinople (currently Bartholomew).

In the countries surveyed that do have a self-governing national Orthodox church, Orthodox respondents are generally more likely to view their own national Orthodox patriarch as the highest authority within Orthodoxy. At the same time, others in some of these countries are more likely to say they view the Moscow patriarch this way (rather than the ecumenical patriarch of Constantinople). Greece is an exception; a majority of Orthodox Greeks view the ecumenical patriarch as the highest Orthodox authority.

Russia, the largest Orthodox country

In 1988, the Soviet Union marked the 1,000th anniversary of the historical event known for bringing what is now known as Orthodox Christianity to Russia and its environs – a mass baptism believed to have occurred in 988 in the Dnieper River in Kiev, which was overseen by Vladimir the Great, ruler of the region then known as Kievan Rus and himself a convert to Orthodoxy.19

Back then, Constantinople was the center of the Orthodox world. But in 1453, the Muslim-led Ottoman Empire conquered the city, and, in the ensuing centuries, Russia’s leaders would come to view themselves as inheritors of the mantle of Orthodox leadership. Moscow, in the words of some observers, had become the “Third Rome,” or leader of the Christian world, following Rome itself and then Constantinople, which was called the “second Rome.”20

Russia’s leadership role in the Orthodox world changed during the Communist era, when Soviet authorities worked to enact atheism across the USSR, putting religious institutions in the country on the defensive. From 1910 to 1970, the Orthodox population in Russia fell by a third, from 60 million to 39 million. Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev even envisioned a day when just a single Orthodox priest would remain in the country.21 But since the end of the Soviet era, Russia’s Orthodox population has rebounded, more than doubling to 101 million. Now, roughly seven-in-ten Russians (71%) identify as Orthodox, up from 37% in 1991.22

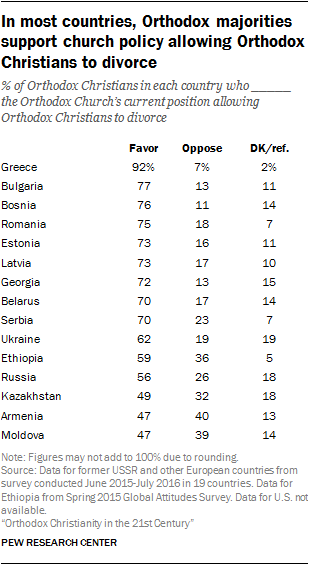

Wide support among Orthodox Christians for church position that allows divorce

Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism have different positions on some controversial issues. For example, Orthodoxy typically allows divorce and remarriage, while Catholicism forbids it.23 And while Orthodoxy allows married men to become priests, the Catholic Church generally does not.24

Most Orthodox Christians support their church’s positions on these issues. Indeed, majorities of Orthodox Christians in 12 of the 15 countries surveyed say they support the church position allowing Orthodox Christians to divorce. This position is most common in Greece, where about nine-in-ten Orthodox Christians (92%) support it.

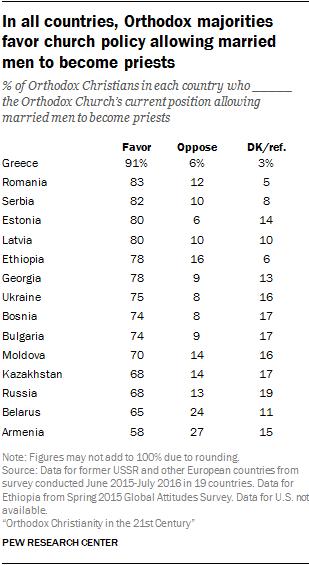

Majorities of Orthodox support church position letting married men be priests

Orthodox majorities in every country surveyed with a substantial Orthodox population say they approve of their church’s policy on permitting married men to become priests. This position – which runs counter to a general Catholic prohibition of married priests – is again most accepted in Greece, where 91% of Orthodox respondents support it. This view is least widespread in Armenia, though even there it is still supported by a majority (58%) of Orthodox Christians.25

Ethiopian Orthodox Christians also generally agree that married men should be allowed to become priests; 78% favor the policy permitting it.

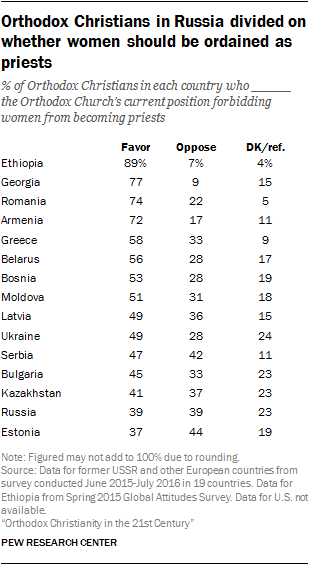

In most countries, Orthodox majorities or pluralities support church policy on women not becoming priests

While some Orthodox jurisdictions allow women to be ordained to the position of deaconess – which entails a variety of official church duties – and others are considering allowing this, Orthodoxy is aligned with Catholicism in forbidding women’s ordination as priests.26

Orthodox majorities or pluralities in many countries support this prohibition, including as many as 89% in Ethiopia and 77% in Georgia. But in a few places, Orthodox Christians are divided. This includes Russia, where 39% favor the current policy and an equal share oppose it, instead saying that women should be ordained as priests. Nearly a quarter of Orthodox Christians in Russia do not take a position on this issue.

On balance, Orthodox women support this prohibition as often as men do. In Ethiopia, for example, 89% of women and men alike favor it, while in Romania it is favored by 74% of both men and women. In Ukraine, 49% of both men and women say women should not be ordained as priests.

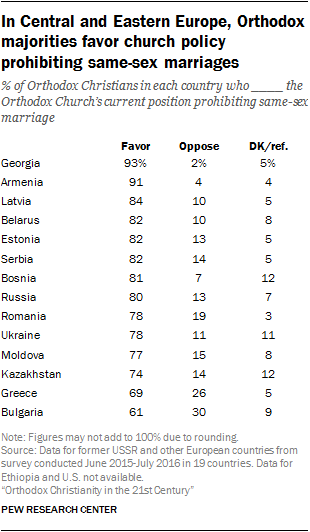

Orthodox ban on same-sex marriage has overwhelming support

The Orthodox Church, like the Roman Catholic Church, does not sanction same-sex marriages. This prohibition is supported by roughly six-in-ten or more Orthodox Christians in every Central and Eastern European country surveyed, including Georgia (93%), Armenia (91%) and Latvia (84%). In Russia, 80% of Orthodox Christians support it.

In most countries surveyed, younger adults favor this policy as much as older people do. A major exception is in Greece, where roughly half (52%) of those ages 18 to 29 support the policy, compared with 78% of those ages 50 and over.

While in some parts of the world, levels of religiosity are strongly tied to views on same-sex marriage, this does not seem to be a major factor among Orthodox Christians. With few exceptions, people who say religion is very important to them are about equally likely to support these church positions as are people who say religion is less important in their lives.

(For more on Orthodox views toward homosexuality and other social issues, see Chapter 4.)

Orthodox Christians in Ethiopia oppose married priests becoming bishops

In Ethiopia, which has the second-largest Orthodox population in the world, Pew Research Center asked two additional questions about specific church policies relating to marriage. Majorities here, too, overwhelmingly agree with these positions.

About seven-in-ten Orthodox Ethiopians (71%) agree with the church position that bars married priests from becoming bishops. (In Orthodoxy, men who are already married are allowed to be ordained as Orthodox priests, but they are not allowed to become bishops.)

An even larger majority (82%) of Orthodox Ethiopians favor Orthodoxy’s prohibition on letting couples marry in an Orthodox church unless both spouses are Christians.