Muslim Americans overwhelmingly embrace both the “Muslim” and “American” parts of their identity. For instance, the vast majority of U.S. Muslims say they are proud to be American (92%), while nearly all say they are proud to be Muslim (97%). Indeed, about nine-in-ten (89%) say they are proud to be both Muslim and American.

Muslim Americans also see themselves as integrated into American society in other important ways. Four-in-five say they are satisfied with the way things are going in their lives in America, and six-in-ten say they have “a lot” in common with most Americans. In addition, a declining share of U.S. Muslims say that “all” or “most” of their close friends are also Muslim.

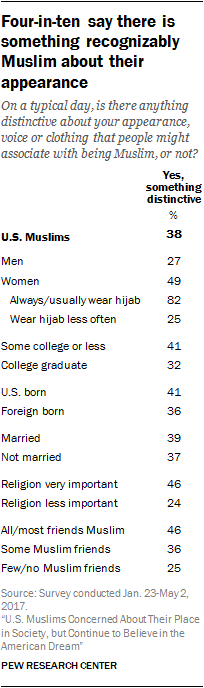

Yet, in other ways, many Muslims feel they stand out in America. For example, about four-in-ten say there is something distinctive about their appearance, voice or clothing that people might associate with being Muslim. This includes most women who regularly wear hijab, but also one-in-four women who do not wear hijab regularly and about a quarter of men who also say there is something distinctively Muslim about their appearance. In addition, three-quarters of Muslim Americans say they feel a strong sense of belonging to the global ummah, or Muslim community, and 80% say they feel a strong tie to Muslim communities in the U.S. – though follow-up interviews highlight the ambiguity of these concepts, even for Muslims who say this.

This chapter also explores other aspects of identity, including what Muslims see as essential to their religious identity and key values and goals in life more broadly.

Most U.S. Muslims proud to be American, satisfied with life

Nine-in-ten U.S. Muslims agree either completely (66%) or mostly (26%) with the statement, “I am proud to be American.” Only a handful of U.S. Muslims disagree with this statement either completely (4%) or mostly (2%).

Muslim immigrants are at least as likely as U.S.-born Muslims to express pride in being American. At the same time, immigrants who have been in the U.S. for longer are somewhat more likely than recent immigrants to say they are proud to be American.

Muslim adults younger than 30 are less likely than older Muslims to say they are proud to be American. The same pattern is evident among the population as a whole.

Among Muslims, pride in being American does not vary significantly based on the importance of religion in their lives. On the other hand, Muslims who say they have a lot in common with most Americans are considerably more likely than those who have less in common to completely agree that they are proud to be American (72% vs. 57%).

When asked how much they have in common with “most Americans,” six-in-ten U.S. Muslims (60%) say they have “a lot” in common. Another 28% say they have “some” in common, and about one-in-ten say they have “not much” (8%) or “nothing at all” (3%) in common with most Americans.

More Muslim men than women (68% vs. 52%) say they have a lot in common with most Americans. And about seven-in-ten Muslim college graduates say they have a lot in common with the average American, compared with only about half of those who have a high school degree or less.

U.S.-born Muslims (68%) are more likely than immigrants (54%) to say they have a lot in common with most Americans, but within these groups there also are important differences. For example, a much smaller share of recent immigrants say they have a lot in common (40%) compared with those who have been in the U.S. longer (72%).

Muslims who say there is something distinctive about their appearance that indicates their Muslim identity are no less likely than those who say there is nothing distinctive about their appearance to say they have a lot in common with most Americans.

Four out of five U.S. Muslims (80%) say they are satisfied with the way things are going in their lives. In fact, Muslims remain about as satisfied with their lives as they were in 2011 (82%). Satisfaction among Muslim Americans is similar to feelings among those in the larger U.S. public.

Life satisfaction is relatively consistent among Muslim men and women, Muslims of varying levels of education, and immigrant and U.S.-born Muslims.

Muslims today less likely to say most of their friends are Muslim

About one-in-three U.S. Muslims say all (5%) or most (31%) of their close friends are Muslim. About half (47%) say some of their friends are Muslim, and roughly one-in-six say hardly any of their friends are Muslim (15%) or that they have no Muslim friends (1%).

A smaller share of Muslims today say that all or most of their friends are Muslim compared with 2011 or 2007, when about half of U.S. Muslims said this.

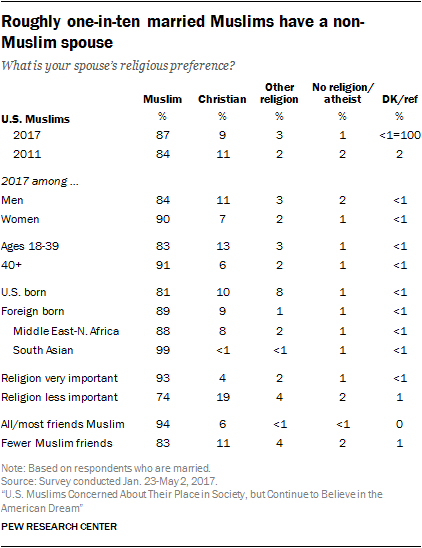

Muslims who say religion is very important to them are much more likely to say that all or most of their friends are Muslim than are those who say religion is less important. As in years past, most married U.S. Muslims have a spouse who is also Muslim (87%). Just 9% have a Christian spouse, 1% are married to someone who has no religious affiliation and 3% are married to someone of another faith. These figures are little changed since 2011.

While differences in question wording make direct comparisons difficult, surveys generally find that those in other religious groups also have a tendency to marry within their faith. Pew Research Center’s 2014 U.S. Religious Landscape Study, for example, found that 90% of married Christians are wedded to another Christian. And a 2013 Pew Research Center survey of U.S. Jews found that 64% of Jews are married to a Jewish spouse.26

Married Muslims who say religion is very important in their lives are far more likely to have a Muslim spouse than those who say religion is less important (93% vs. 74%). And U.S. Muslims whose close friends are mostly or all Muslims are more likely than those with fewer Muslim friends to have a Muslim spouse (94% vs. 83%).

In their own words: What Muslims said about their friends and family

Pew Research Center staff called back some of the Muslim American respondents in this survey to get additional thoughts on some of the topics covered. Here is a sampling of what they said about their Muslim and non-Muslim friends and family: “I don’t have many Muslim friends here in the U.S. simply because I don’t really practice my religion. I don’t go to mosque or many places where I can meet groups of Muslims. So my friendship relationships are mainly with coworkers or things like that. So that’s why I don’t have many Muslim friends. … Ninety-nine percent of people, once they know I am Muslim, they assume my wife had to convert to Islam or that she’s Muslim. And that’s not the case. My wife is not a Muslim; she didn’t convert. That’s an interesting thing – when everyone knows I’m Muslim, they assume she’s Muslim and start acting based on that until I tell them she is not.” – Immigrant Muslim man “I don’t have Muslim friends. I’m originally from Egypt. There’s no Egyptian people around me, and I don’t get along with other nationalities. I don’t have friends at all.” – Muslim man over 60 “I have like a mixture of both Muslim and non-Muslim friends of all different races. I grew up around diversity, and I don’t have anything against non-Muslims. I have non-Muslim friends and coworkers and classmates and everything like that. I pretty much interact with all races and religions.” – Muslim woman under 30

“I actually do have a lot of Muslim friends, but have a lot of non-Muslim friends too. I would say it’s about two-thirds Muslim to one-third non-Muslim. A lot of my Muslim friends I made later in life. That’s because, when I was younger, it was harder to find Muslims I could be friends with. I found it difficult to socialize with Muslims who were socially very liberal. I found it very difficult because I was raised in a very conservative, religious household and that colored how I saw the world. … My dad served four years in the U.S. Air Force and that helped us better socialize with the public and accept our role here in America. And that eventually helped me make more Muslim friends. No matter where they stood on social issues, I could embrace them as friends because they were committed to being in this country as Muslims. … My non-Muslim friends saw me for myself and didn’t see or define me by my religious identity. I wear the hijab, but I have an outgoing personality. So they told me that while they may have judged me at first by my appearance, within five seconds they saw me for who I was.” – Muslim woman in her 40s “I have friends who are Muslim and friends who aren’t Muslim. I’m not sure if I have more Muslim friends or more non-Muslim friends because I don’t think about it. … Religion is just not a big issue for me. So, I don’t care if someone is Christian, Jewish or Muslim or whatever. For me it’s about what’s inside the person. I look for people who match my personality. If I like you, I don’t care about your religion. It’s you I’m interested in.” – Muslim man under 30

[mosque]

Some say they can be recognized as Muslim by appearance

About four-in-ten Muslim Americans say that on a typical day, there is something distinctive about their appearance, voice or clothing that other people might associate with being Muslim. Not only do the vast majority of women who report regularly wearing hijab say this (82%), but about a quarter of Muslim men (27%) and a similar share of Muslim women who wear hijab less often (25%) also say their everyday appearance effectively identifies them as Muslim.

Muslim women who say they are very religious are far more likely to say there is something distinctively Muslim about their appearance than are women who say religion is less important (63% vs. 16%); among men, however, there is no significant difference on this question by religious salience.

In addition, more Muslims in predominantly Muslim friendship circles say there is something distinctive about their appearance compared with those who have few or no Muslim friends.

Nearly all U.S. Muslims are proud to be Muslim, most feel connected to the Muslim community

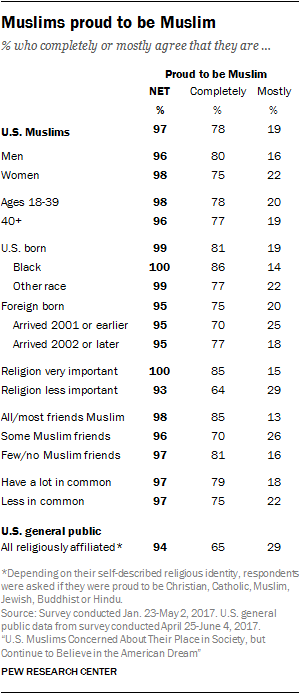

Pride in being Muslim is nearly universal among U.S. Muslims, 97% of whom “completely” or “mostly” agree that they are proud to be Muslim. By comparison, 94% of all religiously affiliated Americans say they are proud to be a member of their faith (e.g., proud to be Christian), although Muslim Americans are more likely than religiously affiliated Americans overall to completely agree that they are proud of their religious identity (78% vs. 65%).

U.S. Muslims who say religion is very important in their lives are especially likely to completely agree that they are proud to be Muslim (85%); among those who say religion is less important, about two-thirds (64%) completely agree that they are proud of their Muslim identity.

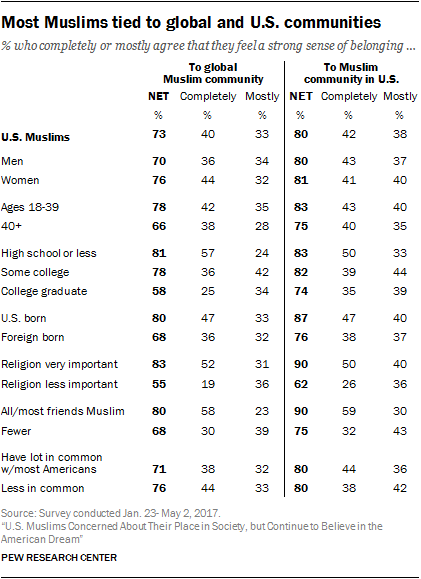

Most U.S. Muslims also feel a sense of belonging to Muslim communities both in the U.S. and around the world.

Nearly three-quarters of Muslim Americans completely (40%) or mostly (33%) agree that they feel a strong sense of belonging to the global Muslim community, or ummah. This view is more common among U.S.-born Muslims than among Muslim immigrants (80% vs. 68%).

Muslims who say religion is very important in their lives are far more likely than those who say religion is less important to say they feel a strong sense of belonging to the Muslim ummah (83% vs. 55%).

Muslims in the U.S. feel modestly more connected to the Muslim community in the U.S. than they do to the global Muslim community. Eight-in-ten completely (42%) or mostly (38%) agree that they feel a strong sense of belonging to the Muslim community in the United States. As with ties to the global Muslim ummah, U.S.-born Muslims, highly religious Muslims and those with many Muslim friends are especially likely to say they feel a connection to the Muslim community in the United States. How much U.S. Muslims feel they have in common with most Americans has little to do with how connected they feel to the Muslim community.

In their own words: What Muslims said about their sense of belonging to the global Muslim ummah and the U.S. Muslim community

Pew Research Center staff called back some of the Muslim American respondents in this survey to get additional thoughts on some of the topics covered. Here is a sampling of what they said about their sense of belonging to the global Muslim ummah and the U.S. Muslim community: “I guess I’m connected to the Muslim ummah, in terms of I belong to the same faith. So if you think about the billions of Muslims out there, I belong to that ummah – whatever that means. … If there is starvation in Somalia I’ll find a way to donate. But I don’t know if I’m that connected with the ummah. You get swallowed up in your life.” – Immigrant Muslim man

[to the Muslim community where I live]

“After 60 years of life, I sympathize with anybody in the world who has problems. It does not matter if they’re Christian, Jewish, Hindu or Muslim or whoever. When I see war and people who are dying or paying their life for something, whether Muslim or not, I feel connected to them.” – Muslim man over 60

“When I’ve traveled overseas … one of things I notice most is that I had more information and knowledge about my religion than my cousins and other family members who lived in a Muslim-majority country, Pakistan. I noticed that I felt more comfortable being Muslim than they did. … When you have freedom of religion and don’t allow it into the political life of a country – then you are free to explore religion, pursue and embrace it or leave it, as you see fit. That’s a beautiful thing to me.” – Muslim woman in her 40s

[The reason for this is a]

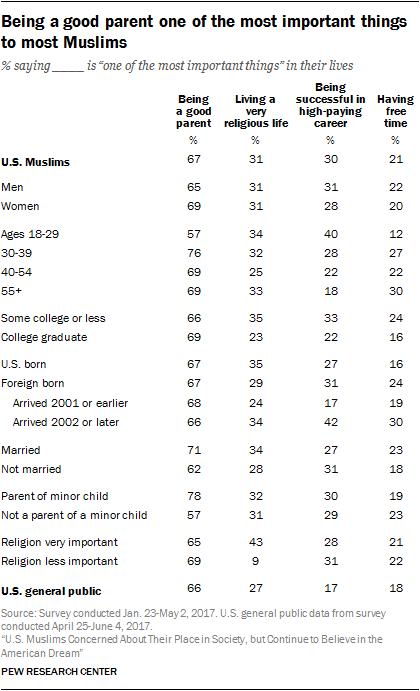

In their personal lives, Muslims prize being good parents – much like other Americans

The survey asked Muslim Americans about the importance of four specific life goals: being a good parent, living a very religious life, being successful in a high-paying career and having free time. Muslims largely mirror the U.S. general public in the sense that being a good parent is more important than any of the other goals asked about in the survey.

The vast majority of Muslim Americans say being a good parent is either “one of the most important things” in their lives (67%) or is “very important, but not one of the most important things” (25%). Very few say being a good parent is “somewhat important” (2%) or “not important” (5%). A similar pattern exists among the larger U.S. public, with fully two-thirds (66%) saying that being a good parent is one of the most important things in their lives and 23% saying it is very important but not one of the most important things.

An especially high share of Muslims with children under 18 currently living at home say being a good parent is one of the most important things (78%), but even among those without minor children at home, more than half (57%) say this as well.

While most Muslims (65%) say religion is very important in their lives, only about half as many (31%) say “living a very religious life” is “one of the most important things” in their life. Three-in-ten Muslims also say that being successful in a high-paying career is one of the most important goals in their life – higher than the comparable share of U.S. adults overall who say this (30% vs. 17%).

Career success is most important among young Muslims and recent immigrants. The importance of a high-paying career is also related to education and household income: About one-in-three respondents with a household income of less than $30,000 say being successful in a high-paying career is one of the most important things in life (35%), compared with just 18% of those with a household income over $100,000.

Having free time is the least important of the four life goals asked about in the survey. One-in-five Muslims say having free time to relax and do what they want is one of the most important things to them, similar to the share of Americans overall who say this.

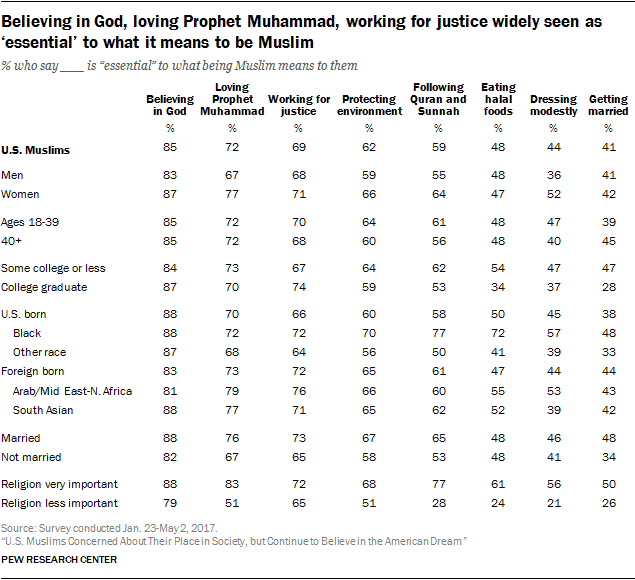

Essentials of being Muslim: Believing in God and loving the Prophet Muhammad, but also working for justice, protecting environment

The survey included a series of questions that asked Muslims whether several beliefs or behaviors are important or essential to what being Muslim means to them, personally. A large majority of Muslims (85%) say believing in God is essential to what being Muslim means to them, while 10% say believing in God is important but not essential to their Muslim identity. Very few (4%) say believing in God is not an important part of what being Muslim means to them.

A 2014 Pew Research Center survey found that U.S. Christians are similarly united in stating that belief in God is essential (86%) or important (10%) to what being Christian means to them.

After belief in God, Muslims place somewhat less emphasis on loving the Prophet Muhammad: Nearly three-quarters (72%) say loving Muhammad is essential to what it means to be Muslim, and another 20% say it is important but not essential.

About seven-in-ten Muslims (69%) say working for justice and equality in society is essential to what it means to be Muslim, and nearly as many (62%) say the same about protecting the environment. By comparison, a majority of U.S. Jews (60%) also say that working for justice and equality is essential to their Jewish identity. And far fewer U.S. Christians (22%) say protecting the environment is essential to what being Christian means to them.

About six-in-ten Muslim Americans (59%) say following the Quran and Sunnah is essential to what being Muslim means to them. Muslims are much more likely to say this than U.S. Jews are to say that observing Jewish law is essential to their Jewish identity (23%). Among Muslims, this view is concentrated among those who say religion is very important to them (77%), while far fewer Muslims who say religion is less important in their lives say following the Quran and Sunnah is essential to their Muslim identity (28%).

Muslims are similarly divided about the importance of eating halal food (see glossary for a definition of halal). Overall, about half of Muslims (48%) say eating halal food is essential to what being Muslim means to them. This view is expressed by roughly six-in-ten Muslims who say religion is very important in their everyday life (61%), but only about a quarter of Muslims who say religion is less important (24%).

Dressing modestly is seen as essential by 44% of Muslims. Here again, this view is most common among the most religious Muslims. The survey also finds that 52% of Muslim women say dressing modestly is essential to what being Muslim means to them, compared with just 36% of Muslim men who say this is essential to their Muslim identity.

Four-in-ten U.S. Muslims say getting married is essential to what being Muslim means to them. There is little difference between men and women on this issue, but married respondents are more likely than those who are not married to say marriage is essential to what being Muslim means to them. In addition, relatively few college-educated Muslims (28%) say getting married is essential.

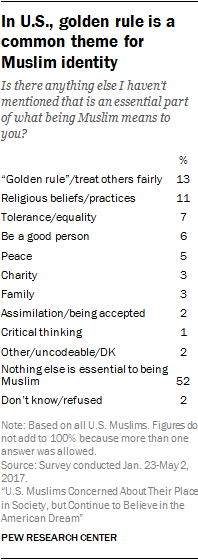

In addition to these eight items, respondents were asked if there was anything else that they personally see as essential to what it means to be Muslim. About one-in-ten mentioned the “golden rule” (13%) or specific ritual practices (11%), such as the daily salah (prayers), as essential aspects of being Muslim. And others mentioned being tolerant (7%), being a good person (6%) and either being peaceful or promoting peace (5%).