Over the last century, the Orthodox Christian population around the world has more than doubled and now stands at nearly 260 million. In Russia alone, it has surpassed 100 million, a sharp resurgence after the fall of the Soviet Union.

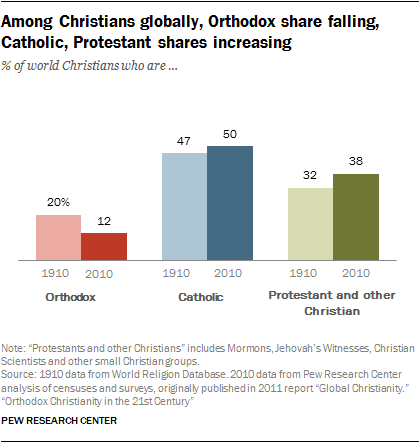

Yet despite these increases in absolute numbers, Orthodox Christians have been declining as a share of the overall Christian population – and the global population – due to far faster growth among Protestants, Catholics and non-Christians. Today, just 12% of Christians around the world are Orthodox, compared with an estimated 20% a century ago. And 4% of the total global population is Orthodox, compared with an estimated 7% in 1910.

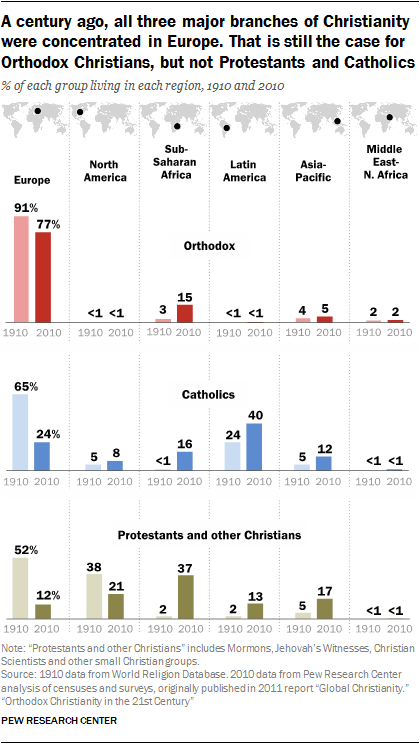

The geographic distribution of Orthodoxy also differs from the other major Christian traditions in the 21st century. In 1910 – shortly before the watershed events of World War I, the Bolshevik revolution in Russia and the breakup of several European empires – all three major branches of Christianity (Orthodoxy, Catholicism and Protestantism) were predominantly concentrated in Europe. Since then, Catholics and Protestants have expanded enormously outside the continent, while Orthodoxy remains largely centered in Europe. Today, nearly four-in-five Orthodox Christians (77%) live in Europe, a relatively modest change from a century ago (91%). By contrast, only about one-quarter of Catholics (24%) and one-in-eight Protestants (12%) now live in Europe, down from an estimated 65% and 52%, respectively, in 1910.1

Orthodoxy’s falling share of the global Christian population is connected with demographic trends in Europe, which has lower overall fertility rates and an older population than developing regions of the world, such as sub-Saharan Africa, Latin America and South Asia. Europe’s population has long been shrinking as a share of the world’s total population, and, in coming decades, it is projected to decline in absolute numbers as well.

Historically, the presence of what is now called Orthodox Christianity in the Slavic portions of Eastern Europe dates to the ninth century, when, according to church tradition, missionaries from the Byzantine Empire’s capital in Constantinople (now Istanbul, Turkey) spread the faith deeper into Europe. Orthodoxy came first to Bulgaria, Serbia and Moravia (which is now part of the Czech Republic), and then, beginning in the 10th century, to Russia. Following the Great Schism between the Eastern (Orthodox) churches and the Western (Catholic) church in 1054, Orthodox missionary activity expanded across the Russian Empire from the 1300s through the 1800s.2

While Orthodoxy spread across the Eurasian landmass, Protestant and Catholic missionaries from Western Europe went overseas, crossing the Mediterranean and the Atlantic. The Portuguese, Spanish, Dutch and British empires, among others, carried Western Christianity (Catholicism and Protestantism) to sub-Saharan Africa, East Asia and the Americas – regions that in the 20th century experienced much faster population growth than Europe. On the whole, Orthodox missionary activity outside Eurasia was less pronounced, although Orthodox churches retained footholds through the centuries in the Middle East, and Orthodox missionaries won some converts in such far-flung places as India, Japan, East Africa and North America.3

Today, the largest Orthodox Christian population outside of Eastern Europe is in Ethiopia. The centuries-old Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church has an estimated 36 million adherents, nearly 14% of the world’s total Orthodox population. This East African outpost of Orthodoxy reflects two broad trends. First, its Orthodox Christian population has grown much faster than Europe’s over the past 100 years. And, second, Orthodox Christians in Ethiopia are more religiously observant, by several common measures, than Orthodox Christians in Europe. This is in line with a broader pattern in which Europeans are, on average, less religiously committed than people in Latin America and sub-Saharan Africa, according to Pew Research Center surveys. (This is true not just of Christians in Europe but also of Europe’s Muslims, who are less religiously observant, as a whole, than Muslims elsewhere in the world.)

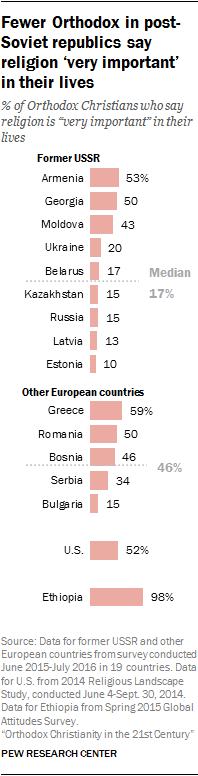

Orthodox Christians in the former Soviet Union generally report the lowest levels of observance among those of their faith, perhaps reflecting the legacy of Soviet repression of religion. In Russia, for example, just 6% of Orthodox Christian adults say they attend church at least weekly, 15% say religion is “very important” in their lives, and 18% say they pray daily. Other former Soviet republics display similarly low levels of religious observance. Together, these countries are home to a majority of the world’s Orthodox Christians.

In sharp contrast, Orthodox Christians in Ethiopia report considerably higher religious observance, on par with other Christians (including Catholics and Protestants) across sub-Saharan Africa. Nearly all Ethiopian Orthodox Christians say religion is very important to them, while roughly three-quarters report attending church weekly or more often (78%) and about two-thirds say they pray daily (65%). (For more information on Ethiopia’s Orthodox Tewahedo Church, see this sidebar.)

Orthodox Christians living in Europe outside the former Soviet Union show somewhat higher levels of religious observance than those in the former Soviet republics, but they are still far less observant than Ethiopia’s Orthodox community. In Bosnia, for example, 46% of Orthodox Christians say religion is very important in their lives, while 10% say they attend church weekly or more often, and 28% report that they pray daily.

Orthodox Christians in the United States, who make up roughly 0.5% of the overall U.S. population and include many immigrants, display moderate levels of religious observance, lower than in Ethiopia but higher than most European countries, at least by some measures. About half (52%) of Orthodox Christian adults in the United States say religion is very important to them, roughly one-in-three (31%) report that they attend church weekly or more, and a slim majority say they pray daily (57%).

In addition to their shared history and liturgical traditions, what do these disparate communities have in common today?

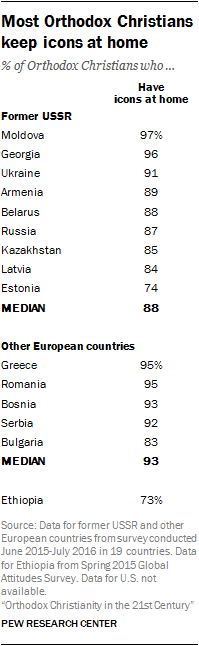

One nearly universal practice among Orthodox Christians is the veneration of religious icons. Most Orthodox Christians around the world say they keep icons or other holy figures in their homes.

In fact, having icons is among the few indicators of religiosity on which Central and Eastern European Orthodox Christians surpass Orthodox Ethiopians in surveys. Across 14 countries in the former Soviet Union and elsewhere in Europe with large Orthodox populations, the median share of Orthodox Christians who say they have icons at home is 90%, while in Ethiopia, the share is 73%.

Orthodox Christians around the world also are linked by a married, all-male priesthood; church structures headed by numerous national patriarchs and archbishops; recognition of divorce; and moral conservatism on issues such as homosexuality and same-sex marriage.

These are among the key findings of a new Pew Research Center study of Orthodox Christianity around the world. The data in this report come from a variety of surveys and other sources. Data on the religious beliefs and practices of Orthodox Christians in nine countries across the former Soviet Union and five other countries in Europe, including Greece, are from surveys conducted by Pew Research Center in 2015-2016. In addition, the Center has recent data on many (though not all) of the same survey questions among Orthodox Christians in Ethiopia and the United States. Together, these surveys cover a total of 16 countries, collectively representing about 90% of the estimated global Orthodox population. In addition, population estimates are available for all countries based on information gathered for the 2011 Pew Research Center report “Global Christianity” and the 2015 report “The Future of World Religions: Population Growth Projections, 2010-2050.”

Wide support among Orthodox for the church’s teachings on priesthood, divorce

While they vary widely in their levels of religious observance, Orthodox Christians around the world are largely united in their affirmation of some distinctive church policies and teachings.

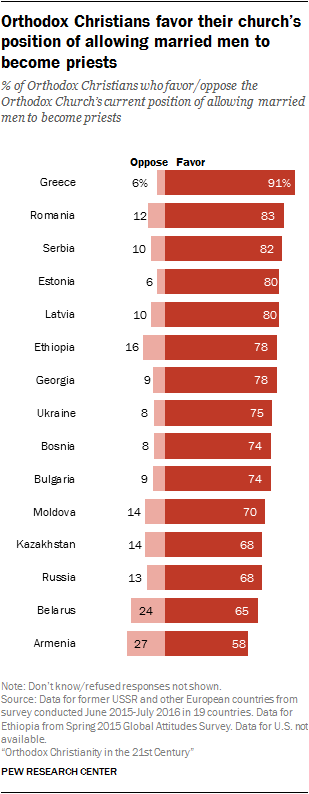

Today, majorities of Orthodox Christians in every country surveyed say they favor their church’s current practice of allowing married men to become priests, which contrasts with the Catholic Church’s general requirement of celibacy for priests. (Lay Catholics in some countries prefer allowing married priests; in the United States, for example, 62% of Catholics say the Catholic Church should allow priests to get married.)

Similarly, most Orthodox Christians also say they support the church’s stance on recognizing divorce, which also differs from Catholicism’s position.

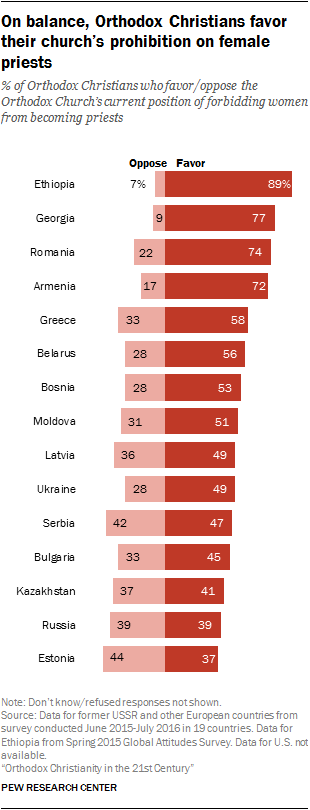

Orthodox Christians also broadly favor a number of church positions that happen to align with those of the Catholic Church, such as the prohibition on women’s ordination. In fact, there appears to be more agreement with this position within Orthodoxy than within Catholicism, where majorities in some places say women should be able to become priests. For example, in Brazil, which has the world’s largest Catholic population, most Catholics say the Catholic Church should allow female ordination (78%). Similarly, in the United States, 59% of Catholics say the Catholic Church should allow women priests.

Orthodox opinion is closely divided on the issue of female ordination in Russia and some other countries, but in no country surveyed do a majority of Orthodox Christians support ordaining women as priests. (In Russia and some other countries, roughly a fifth or more of respondents do not express an opinion on women’s ordination.)

Orthodox Christians also are broadly united against the idea of the church performing same-sex marriages (see Chapter 3).

Overall, Orthodox Christians see plenty of common ground between their own faith and Catholicism. When asked if Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism “have a lot in common” or “are very different,” most Orthodox Christians across Central and Eastern Europe respond that the two faiths have a lot in common. For their part, Catholics in the region also tend to see the two traditions as more similar than different.

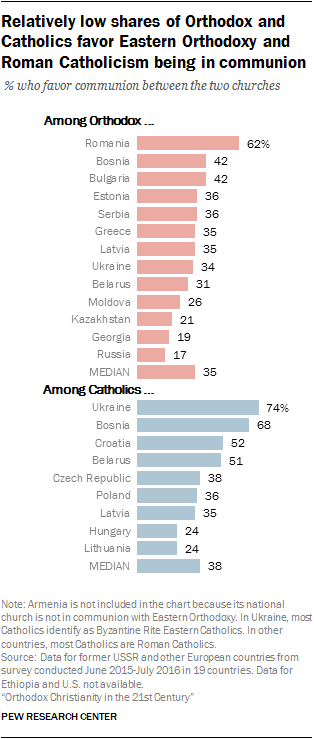

But this perceived kinship only goes so far; there is limited support among Orthodox Christians for “being in communion again” with Roman Catholics. Formal schism owing to theological and political disputes has divided Eastern Orthodoxy from Roman Catholicism since the year 1054; while some clerics on both sides have tried for half a century to foster reconciliation, the view that the churches should reunite is a minority position across most of Central and Eastern Europe.4

In Russia, just one-in-six Orthodox Christians (17%) say they want Eastern Orthodoxy to be in communion with the Roman Catholic Church, the lowest level of support for reconciliation found in any of the national Orthodox populations surveyed. Only in one country, Romania, do a majority of respondents (62%) express support for reunification of the Eastern and Western churches. Across the region, many Orthodox Christians decline to answer this question, perhaps reflecting a lack of familiarity with the issue or uncertainty about what communion between the two churches would entail.

This pattern may be linked to a wariness of papal authority by Orthodox Christians. While most Orthodox Christians across Central and Eastern Europe say Pope Francis is improving relations between Catholics and Orthodox Christians, far fewer express a positive opinion of Francis overall. Views on this topic also may be bound up with geopolitical tensions between Eastern and Western Europe. Orthodox Christians in Central and Eastern Europe tend to orient themselves, both politically and religiously, toward Russia, while Catholics in the region generally look toward the West.

Overall, in Central and Eastern Europe, Orthodox support for reconciliation with Catholicism is about as high as Catholic support for it. But in countries with substantial shares of both Orthodox Christians and Catholics, Catholics tend to be more supportive of a return to communion with Eastern Orthodoxy. For example, in Bosnia, a majority of Catholics (68%) favor communion, compared with a minority (42%) of Orthodox Christians. A similar pattern is seen in Ukraine and Belarus.

Sidebar: Eastern Orthodoxy vs. Oriental Orthodoxy

Not only are there important theological and doctrinal differences among Orthodox Christians, Catholics and Protestants, but there also are differences within Orthodoxy, which conventionally is divided into two major branches: Eastern Orthodoxy, most of whose adherents live in Central and Eastern Europe, and Oriental Orthodoxy, most of whose adherents live in Africa.

One theological difference has to do with the nature of Jesus and how to articulate Jesus’s divinity – part of a theological field of study called Christology. Eastern Orthodoxy, as well as Catholicism and Protestantism, teach that Christ is one person in two natures: both fully divine and fully human, accepting the language from an early Christian gathering called the Council of Chalcedon, held in 451. But Oriental Orthodoxy, which is considered “non-Chalcedonian,” teaches that Christ’s divine and human natures are unified, not separated.5

Oriental Orthodoxy has separate self-governing jurisdictions in Ethiopia, Egypt, Eritrea, India, Armenia and Syria, and it accounts for roughly 20% of the worldwide Orthodox population. Eastern Orthodoxy is split into 15 jurisdictions heavily centered in Central and Eastern Europe, accounting for the remaining 80% of Orthodox Christians.6

Data on the beliefs, practices and attitudes of Orthodox Christians in Europe and the former Soviet Union come from surveys conducted between June 2015 and July 2016 through face-to-face interviews in 19 countries, including 14 for which samples of Orthodox Christians were large enough for analysis. Findings from these surveys were released in a major Pew Research Center report in May 2017, but additional analysis (including results from Kazakhstan, which were not included in the initial report) is included throughout this report.

Orthodox Christians in Ethiopia were polled as part of Pew Research Center’s 2015 Global Attitudes survey, as well as a 2008 survey on religious beliefs and practices of Christians and Muslims in sub-Saharan Africa; Orthodox Christians in the U.S. were surveyed as part of Pew Research Center’s 2014 U.S. Religious Landscape Study. Since the methodology and the mode of the U.S. study are different from surveys conducted in other countries, comparisons between them are made cautiously. In addition, due to differences in questionnaire content, data are not available from all countries for every question analyzed in this report.

The largest Orthodox populations that were not surveyed are in Egypt, Eritrea, India, Macedonia and Germany. Despite the lack of survey data on Orthodox Christians in these countries, they are included in the population estimates in this report.

Although Orthodox Christians comprise roughly 2% of the Middle East’s population, logistical concerns make it difficult to survey these groups. Egypt has the Middle East’s largest Orthodox population (an estimated 4 million Egyptians, or 5% of the population), mainly members of the Coptic Orthodox Church. Additional data on the demographic characteristics of Middle Eastern Orthodox Christians, including their declining shares over time, can be found in Chapter 1.

Historical population estimates for 1910 are based on Pew Research Center analysis of data from the World Christian Database, which was compiled by The Center for the Study of Global Christianity at the Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary. The estimates from 1910 provide a vantage point on worldwide Orthodoxy at an important historical moment, preceded by an especially active period for Orthodox missionaries across the Russian Empire and shortly before war and political upheaval threw most Orthodox populations into tumult.7 By the end of the 1920s, the Russian, Ottoman, German and Austro-Hungarian empires had all ceased to exist – replaced by new, self-governing nations, as well as, in some cases, self-governing national Orthodox churches. Meanwhile, the Russian Revolution of 1917 ushered in communist governments that persecuted Christians and other religious groups for the length of the Soviet era.

This report, funded by The Pew Charitable Trusts and the John Templeton Foundation, is part of a larger effort by Pew Research Center to understand religious change and its impact on societies around the world. The Center previously has conducted religion-focused surveys across sub-Saharan Africa; the Middle East-North Africa region and many other countries with large Muslim populations; Latin America and the Caribbean; Israel; and the United States.

Other key findings in this report include:

- Orthodox Christians in Central and Eastern Europe widely favor protecting the natural environment for future generations, even if this reduces economic growth. In part, this view may be a reflection of the environmentalist stance of Patriarch Bartholomew of Constantinople, who is considered a theological authority in Eastern Orthodoxy. But environmentalism seems to be a widespread value across the Central and Eastern European region as a whole. Indeed, a majority of Catholics in the region also say the natural environment should be protected, even if this reduces economic growth. (For more details, see Chapter 4.)

- Most Orthodox-majority countries in Central and Eastern Europe – including Armenia, Bulgaria, Georgia, Greece, Romania, Russia, Serbia and Ukraine – have national patriarchs who are regarded as preeminent religious figures in their home countries. In all but Armenia and Greece, pluralities or majorities see the national patriarchs as the highest authority of Orthodoxy. For example, in Bulgaria, 59% of Orthodox Christians say they recognize their national patriarch as the highest authority of the church, although 8% also point to Patriarch Bartholomew of Constantinople, who is known as the ecumenical patriarch across Eastern Orthodoxy. Patriarch Kirill of Russia also is highly regarded among Orthodox Christians in the region – even outside Russian borders – a trend that is in line with Orthodox Christians’ overall affinity for Russia. (For Orthodox Christians’ views on patriarchs, see Chapter 3.)

- U.S. Orthodox Christians are much more accepting of homosexuality than are Orthodox Christians in Central and Eastern Europe and Ethiopia. About half of U.S. Orthodox Christians (54%) said same-sex marriage should be legal in a 2014 survey, similar to the share of Americans overall who took that position in that year (53%). By comparison, the vast majority of Orthodox Christians across Central and Eastern Europe are opposed to same-sex marriage. (For Orthodox Christians’ views on social issues, see Chapter 4.)

- Overwhelming majorities of Orthodox Christians in Central and Eastern Europe say they have been baptized, even though many came of age during Soviet times. (For more on religious practices of Orthodox Christians, see Chapter 2.)

Correction: The chart “Relatively low shares of Orthodox and Catholics favor Eastern Orthodoxy and Roman Catholicism being in communion” has been updated to correct the share of Catholics in Bosnia saying the two churches should be in communion.

Correction: The chart “A century ago, all three major branches of Christianity were concentrated in Europe. That is still the case for Orthodox Christians, but not Protestants and Catholics” has been updated to correct the share of Orthodox living in Asia-Pacific in 2010.

The share of Orthodox living in Central and Eastern Europe has been corrected in Chapter 1.