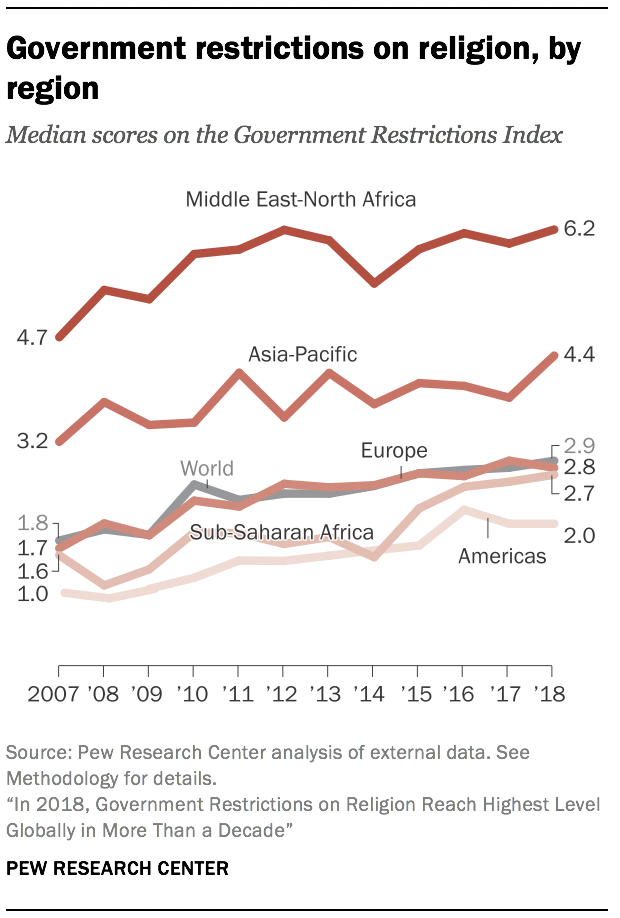

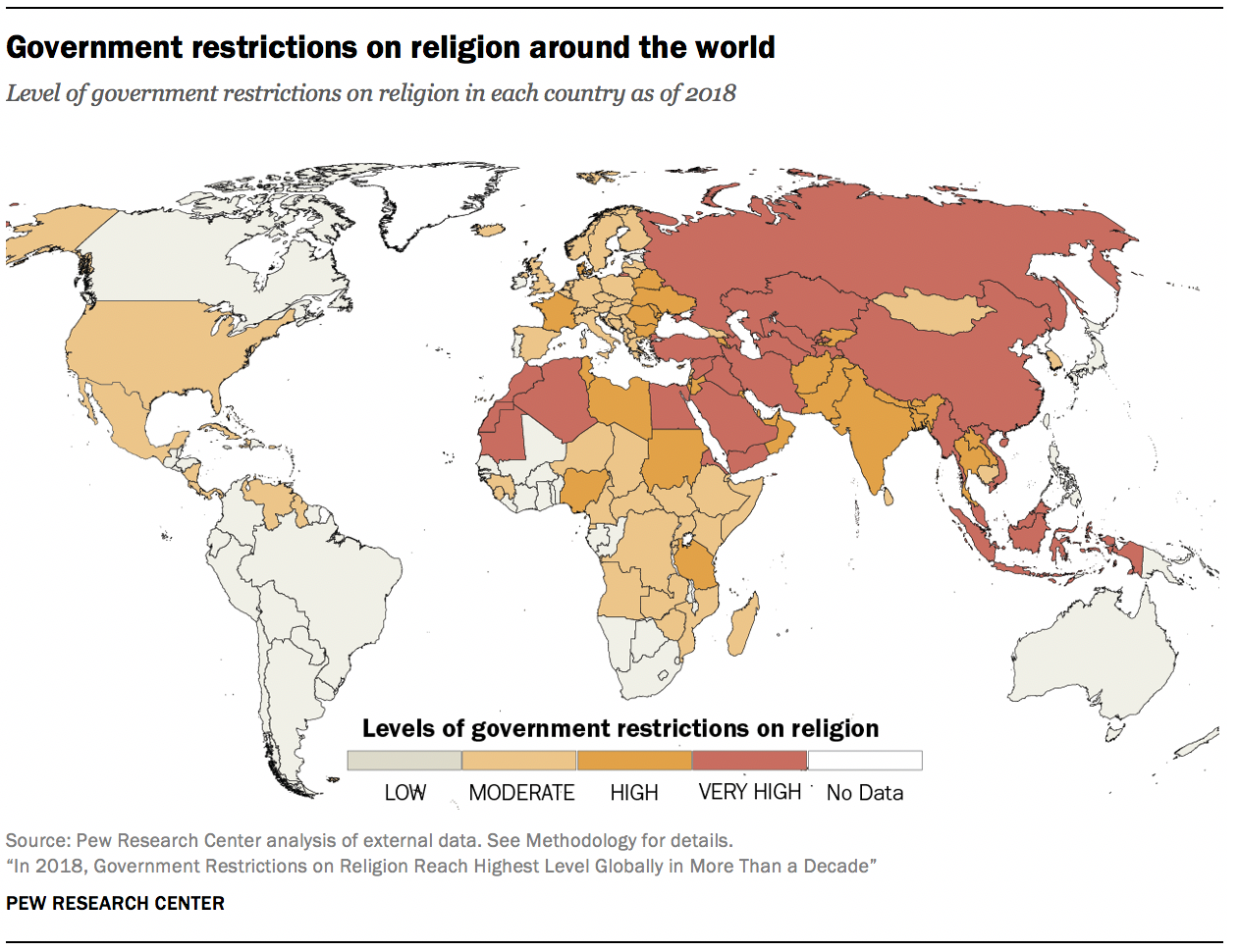

Government restrictions by region

In 2018, the global median level of government restrictions on religion reached a peak at 2.9 after remaining stable at 2.8 in 2016 and 2017. Three out of five regions in the study experienced increases (Asia and the Pacific, the Middle East and North Africa, and sub-Saharan Africa), while Europe had a slight decrease and the median score for the Americas remained about the same.

As in all prior years of the study, the Middle East and North Africa continued to have the highest median level of government restrictions (6.2 out of 10 on the Government Restrictions Index, or GRI). All 20 states in the region had some level of harassment of religious groups and interference in worship. Qatar, for example, continued to prohibit non-Muslim groups from public worship, displaying religious symbols and proselytizing.42 And in Sunni-majority Egypt, authorities continued to restrict access to the tomb of Imam Al-Hussein, the grandson of Islam’s Prophet Muhammad and an important figure for Shiite Muslims. The closure occurred, as it has in recent years, during the Shiite commemoration of Ashura, and although the Egyptian government claimed it was due to construction, some media reported that it was an attempt to limit Shiite religious rituals.43

The largest overall increase in levels of government restrictions on religion occurred in the Asia-Pacific region, where the median GRI score among the region’s 50 countries moved from 3.8 to 4.4 – an all-time high (see Overview for details). While this increase was driven partly by instances of government use of force against religious groups in more countries (especially at “low levels”), there also were increased reports of restrictions on wearing religious symbols or headscarves in the region.

In total, 19 out of 50 countries in the Asia-Pacific region (38%) had some reported restrictions on wearing religious symbols and headscarves, an increase from 14 countries (28%) the previous year. In Australia, for example, a judge did not allow a woman to wear a niqab in the court’s public spectator gallery during her husband’s trial on charges of terrorism.44 And in Thailand, a public school located on a Buddhist temple property in the predominantly Muslim southern part of the country refused to let a group of Muslim students wear headscarves to school.45 In Turkey, by contrast, students and parents claimed a school principal in the city of Urfa threatened that female students would receive failing grades if they did not wear head coverings.46

In sub-Saharan Africa, the median GRI score ticked up from 2.6 to 2.7 between 2017 and 2018. As discussed in the Overview, government harassment and hostility toward minority religious groups was reported in slightly more countries across the region. Although government force against religious groups fell overall, 20 countries (42%) in sub-Saharan Africa still experienced some level of government force toward religious groups in 2018.

In Kenya, for example, counterterrorism efforts led to the disproportionate targeting of Muslims, particularly ethnic Somalis in areas along the border with Somalia. The government actions included “extrajudicial killing, torture and forced interrogation, arbitrary arrest, detention without trial, and denial of freedom of assembly and worship,” according to the U.S. State Department.47

And in Eritrea, where the government has officially recognized only four religious groups (the Eritrean Orthodox Church, Sunni Islam, the Roman Catholic Church, and the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Eritrea) since 2002, hundreds of prisoners continued to be detained on the basis of their religion. An estimated 345 church leaders and 800 to 1,000 lay members were imprisoned, according to a UK-based Christian organization, and 53 Jehovah’s Witnesses reportedly remained in detention for refusing military service as a matter of conscientious objection.48 The government also detained up to 800 protesters, according to human rights groups, after the death in prison of a prominent Muslim who had been arrested for speaking out against a government plan to expropriate an Islamic school.49

Europe’s median GRI score dipped slightly, from 2.9 in 2017 to 2.8 in 2018, partly because of fewer reports that governments failed to protect religious groups from abuse. For example, in 2017, Jewish groups had criticized a French prosecutor’s delay in indicting a man for beating a 65-year-old Jewish woman and pushing her out a window, as well as the prosecutor’s initial exclusion of anti-Semitism as a motive for the murder.50 But no such complaints were reported in 2018, even though there were continued reports of harassment of Jews because of their religion. In fact, the French government announced a three-year national action plan (spanning 2018 to 2020) to combat anti-Semitism and racism, including countering online hate content and improving victim protection services. At the same time, however, the government continued to restrict religion through its counterterrorism measures, closing down mosques and expelling preachers it deemed radical.51

Throughout Europe, government use of force – which includes confiscation or damage of property, detentions, displacement, physical abuse or killings – against religious groups increased slightly, especially at low levels: The number of countries where fewer than 10 such incidents were recorded during the year increased from 10 in 2017 to 15 in 2018, while the number of countries where no such incidents were reported dropped from 31 to 28.

For instance, in North Macedonia (formerly the Republic of Macedonia), authorities seized the passport of the archbishop of the Orthodox Archbishopric of Ohrid – a religious group the government has denied official recognition – and prevented him from crossing the border into Greece. The archbishop filed complaints with various European entities, and by the end of the year, the passport had been returned without explanation.52

There was more widespread use of force in some parts of the region. In Russia, for example, the government continued targeting “nontraditional” religious groups, including Jehovah’s Witnesses, who were formally banned in 2017. Throughout 2018, Jehovah’s Witnesses in Russia faced raids on their homes, detentions, travel restrictions and investigations, and an estimated $90 million of church property was confiscated.53

The Americas continued to have lower levels of government restrictions on religion than any other major region; its median score was stable (2.0 in both 2017 and 2018). Still, 86% of countries in the Americas (30 out of 35) experienced some level of government harassment against religious groups, and 80% (28 countries) had reports of authorities interfering in worship in some way.

In Nicaragua, according to Amnesty International, the government “committed or permitted” serious human rights violations, including attacks on the Catholic Church and its clergy, especially those who helped protect protesters. For example, in July, police conducted a 15-hour attack on a church in the capital city of Managua that was providing shelter to student protesters; two people died and at least 10 were injured in the police action. And in September, a deputy chief of police assaulted a priest for asking government supporters to turn down ruling-party propaganda music playing outside the church during a funeral.54

In the Bahamas and Jamaica, meanwhile, the Afro-Caribbean religious practice of Obeah remains illegal.55 At the same time, Antigua and Barbuda decriminalized marijuana use – which Rastafarians argue is integral to their religious rituals – and publicly apologized for discriminating against the group in the past (although Rastafarians continued to face obstacles to using marijuana ceremonially in other parts of the region).56

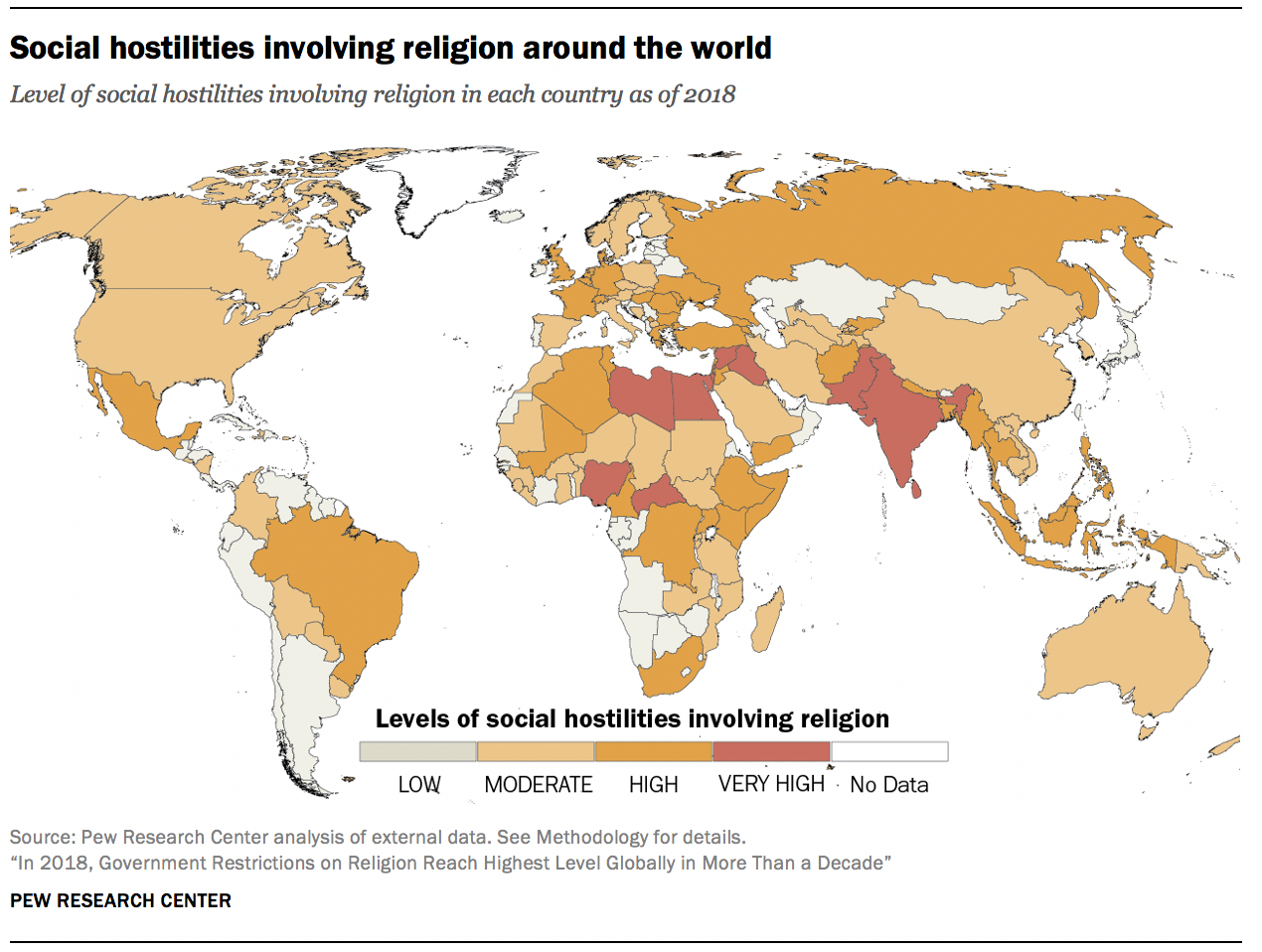

Social hostilities by region

In 2018, the global median level of social hostilities declined slightly from 2.1 to 2.0, though it remained close to the all-time high reached in the previous year. The Americas was the only region in 2018 to experience an increase in its median score on the 10-point Social Hostilities Index (SHI). The Asia-Pacific region’s median score remained about the same, while sub-Saharan Africa, Europe and the Middle East-North Africa regions all experienced declines – with the Middle East and North Africa’s score near its all-time low of 3.7, established in the baseline year of 2007.57

The median SHI score in the Americas was 0.7, an increase from 0.4 in 2017. Still, the Americas continued to have the lowest overall level of social hostilities of the five geographic regions analyzed in the study.

The largest increase within the Americas occurred in El Salvador, where in March, during Catholic Holy Week, armed men robbed a priest and his companions on their way to Mass and killed the priest.58 Then, in July, Salvadoran gang members killed a Protestant pastor for reportedly persuading six members to leave the gang and join his congregation. Gang members also extorted money from congregations in exchange for letting them operate, or in some cases made them divert charitable donations to gang members’ families.59

The United States experienced a decrease in its overall social hostilities score, but it was one of the only countries in the Americas with religion-related terrorist activity in 2018.60 In October, a man attacked a synagogue in Pittsburgh and shot worshippers during services, killing 11 people and injuring six others in one of the deadliest assaults on Jews in American history. Prior to the attack, the shooter was reported to have posted anti-Semitic statements on social media protesting a nonprofit Jewish organization’s resettlement of refugees in the U.S.61

In sub-Saharan Africa, the median level of social hostilities involving religion fell from 2.2 to 2.0 between 2017 and 2018, while Europe’s median score on the SHI dropped from 2.6 to 2.2, and the Middle East-North Africa saw a decline from 4.3 to 3.8. There were fewer countries in all these regions with reported attacks on individuals who practice a religion that goes against the majority faith in the country (see SHI.Q.10 in Appendix D). Sub-Saharan Africa also had fewer countries with reports of hostilities over enforcing religious norms (SHI.Q.9).

The median social hostilities score for Asia and the Pacific remained at 2.1 in 2018, the same as in 2017.