Indians live religiously segregated lives. Most form friendship circles within their own religious community and marry someone of the same faith; interreligious marriages are very uncommon. Indeed, a majority of Indians say it is very important to stop both women and men in their community from marrying outside their religion.

Generally, Indians do not object to members of other religious groups living in their village or neighborhood. Still, a substantial share of Indian adults say they would be unwilling to accept members of certain other religions as neighbors.

These kinds of preferences for living separate lives vary by religion. While large shares of Hindus and Muslims say all their close friends share their religion, Christians and Buddhists tend to have slightly more mixed social circles and to attach less importance to stopping interreligious marriage.

Geography is also a factor. People in the South of India tend to be more religiously integrated and less opposed to interreligious marriages. For example, Hindus who live in the South are more likely than Hindus in other regions to say they would accept a Muslim or a Christian as a neighbor. The Central region of the country, by contrast, stands out as highly religiously segregated.

Views on religious segregation also are related to levels of education. In general, Indians with a college degree are more inclined to accept people of other faiths as neighbors, and less opposed to religious intermarriage, than are Indians who have less education.

Among Hindus in particular, attitudes toward interreligious marriages and neighborhoods are closely tied to views on politics and national identity. Hindus who strongly favor religious segregation – those who say that all their close friends are Hindus, that it is very important to stop Hindus from marrying outside the faith and that they would not accept people of some other faiths as neighbors – are much more likely than other Hindus to take the position that it is very important to be a Hindu to be “truly” Indian. They are also more likely to have voted for the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) in the 2019 parliamentary elections.

Members of both large and small religious groups mostly keep friendships within religious lines

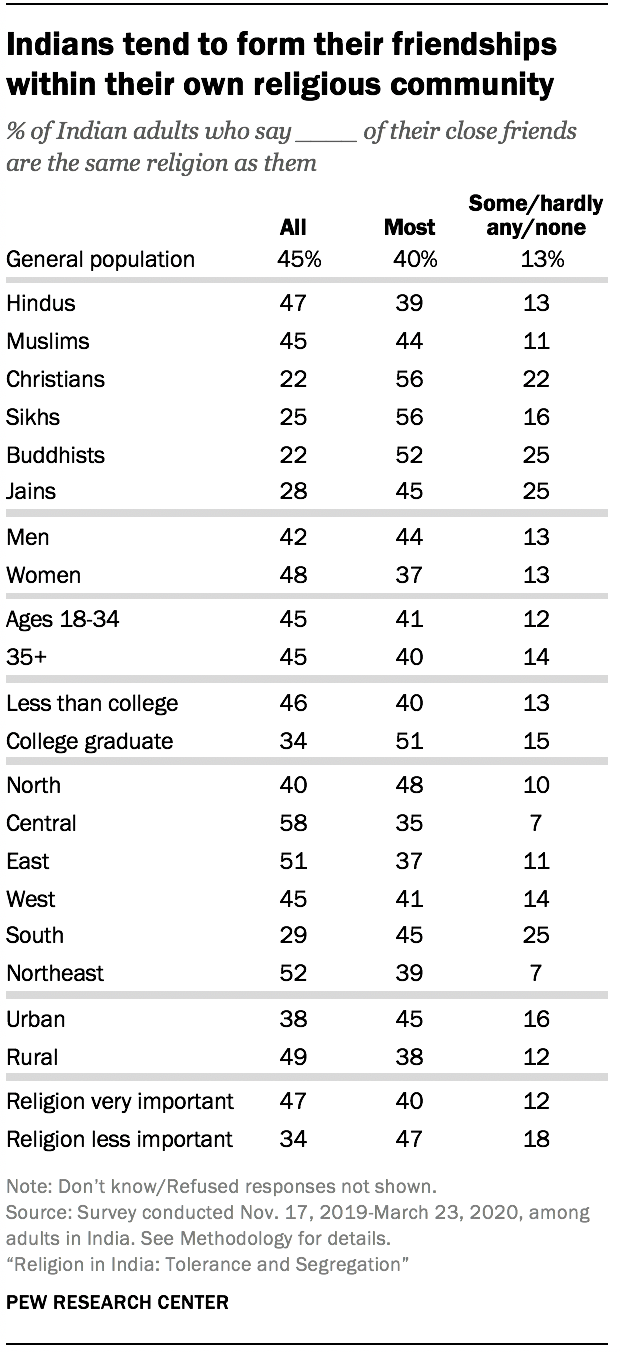

In India, a person’s religion is typically also the religion of that person’s close friends. A large majority of Indian adults say that either “all” (45%) or “most” (40%) of their close friends have the same religion they do. Relatively few adults (13%) have a more mixed friendship circle, saying that “some,” “hardly any” or “none” of their friends share their faith.

In India, a person’s religion is typically also the religion of that person’s close friends. A large majority of Indian adults say that either “all” (45%) or “most” (40%) of their close friends have the same religion they do. Relatively few adults (13%) have a more mixed friendship circle, saying that “some,” “hardly any” or “none” of their friends share their faith.

Nearly half of Hindus (47%) say all of their close friends share their religious identity, and an additional 39% say most of their friends are fellow Hindus. But the country’s religious minorities also have friendship circles consisting largely of people of their own religion. For example, the vast majority of Muslims (88%) say all or most of their friends are Muslim.

People belonging to smaller religious groups are less likely than Hindus and Muslims to say all their friends are of the same religion. Still, Christians, Sikhs, Buddhists and Jains also tend to form friendships mostly within their group. For example, among Jains – who make up less than 0.5% of India’s population – 72% say their close friends are entirely (28%) or mostly (45%) other Jains.

Generally, Indians who have a college degree and those who live in urban areas are more likely than others to have a mixed circle of friends. Religious observance is a factor as well: People who are more observant are more inclined to be friends only with people who share their religion. For example, among Indians who say religion is very important in their lives, nearly half (47%) say all their friends share their religion, compared with about a third (34%) who say this among those who are less religious.

Men are somewhat more likely than women to have a religiously mixed friendship circle. But age makes little difference: Within the population as a whole, as well as within the major religious groups, younger adults are about as likely as older people to say all their close friends share their same religion.

Regionally, people in the South are less likely than those in other regions to say all their close friends share their religion (29%). Among Hindus in the South, 31% say all their close friends are also Hindu, compared with 47% of Hindus nationally who say their friendship circle is exclusively Hindu. An even lower share of Muslims in the region (19%) say all their friends are Muslims, while 45% of Muslims across the country say all their close friends are fellow Muslims.

Most Indians are willing to accept members of other religious communities as neighbors, but many express reservations

Majorities in India say, hypothetically, that they would be willing to accept members of other religious groups as neighbors.

Majorities in India say, hypothetically, that they would be willing to accept members of other religious groups as neighbors.

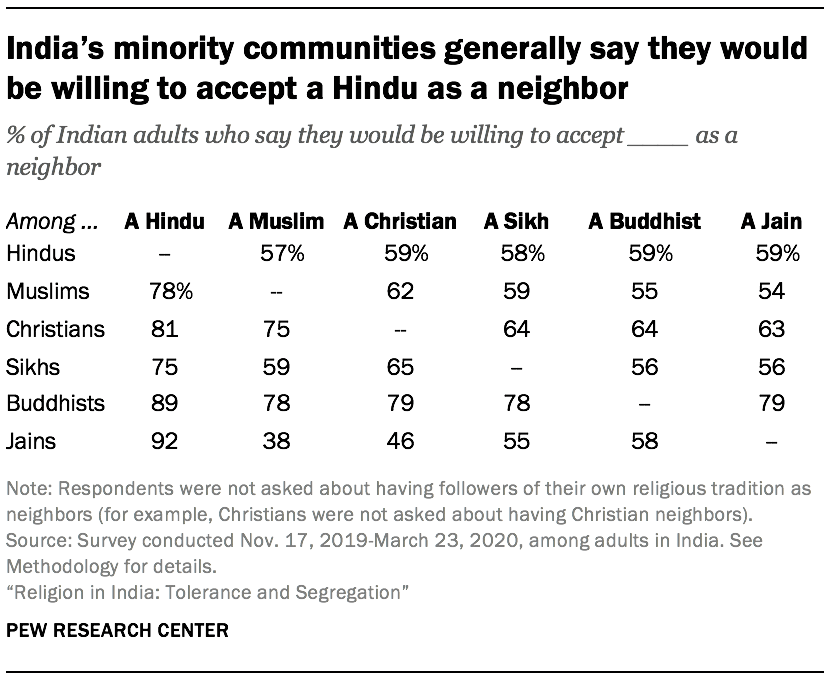

For instance, large majorities of Muslims (78%) and members of other religious minority communities say they would be willing to live near a Hindu – which may be unsurprising given that Hindus make up a large majority of India’s population.

Among Hindus, most say they would be willing to live near a member of a religious minority, such as a Muslim (57%), a Christian (59%) or a Jain (59%). But many Hindus express reservations about such an arrangement. For example, 36% of Hindus say they would not be willing to live near a Muslim, and 31% say they would not want a Christian living in their neighborhood. Jains are even more likely to express such views: 54% would not accept a Muslim as a neighbor, and 47% say the same about Christians.

By contrast, Buddhists are most likely to voice acceptance of other religious groups. Roughly eight-in-ten Buddhists in India say they would be willing to accept a Muslim, Christian, Sikh or Jain as a neighbor, and even more (89%) say they would accept a Hindu.

In a few cases, considerable shares of people decline to answer these questions, possibly because of a lack of familiarity with particular religious groups. For example, 18% of Hindus in Southern India do not answer whether they would be willing to accept a Sikh as a neighbor, perhaps because Sikhs are largely concentrated in the North. Similarly, substantial shares of Muslims in several regions are unsure or don’t clearly say whether they would be willing to live next to a Jain; India’s Jains are most heavily concentrated in the West.

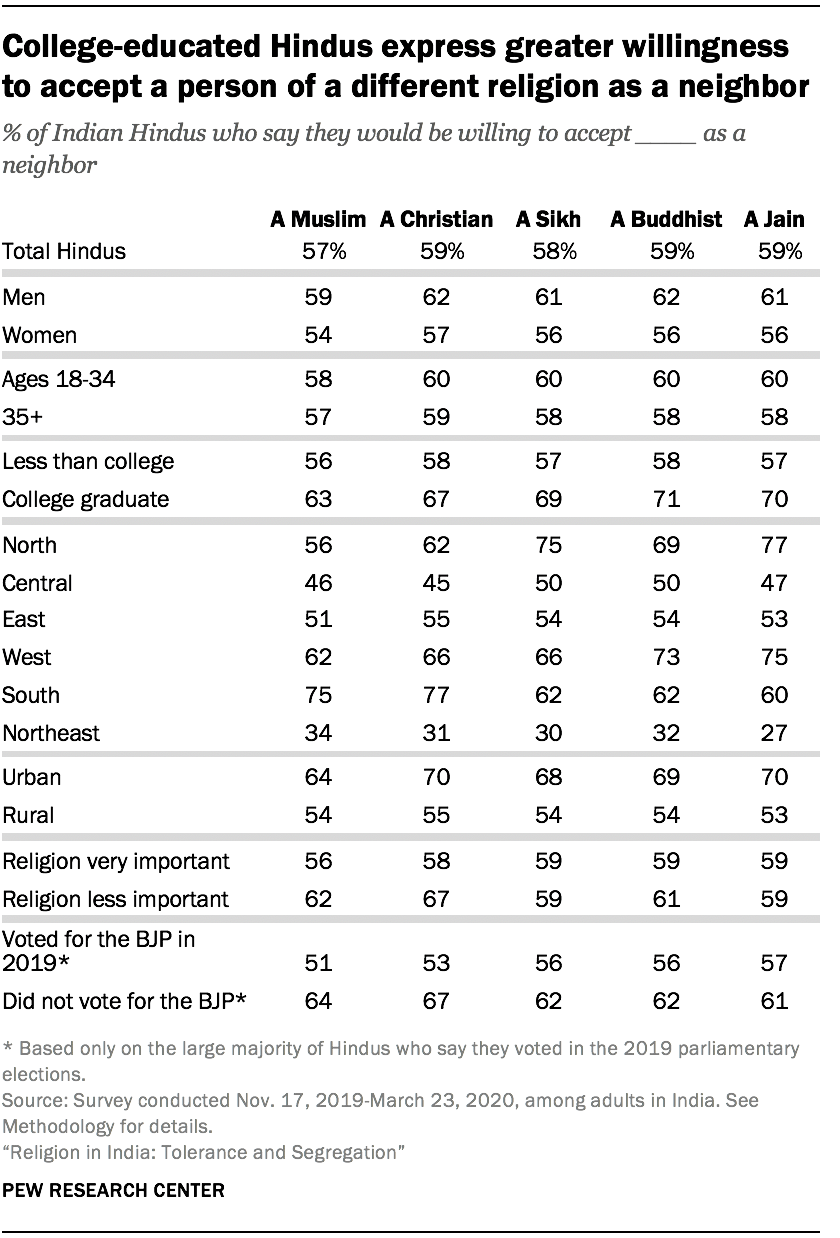

Generally, people who have more education are more likely to say they would accept people of other religions as neighbors. For example, 63% of Hindus with a college degree say they would be willing to accept a Muslim in their neighborhood, compared with 56% of those with less education. Among Hindus, those who live in urban areas of the country also express higher levels of tolerance in this respect.

Generally, people who have more education are more likely to say they would accept people of other religions as neighbors. For example, 63% of Hindus with a college degree say they would be willing to accept a Muslim in their neighborhood, compared with 56% of those with less education. Among Hindus, those who live in urban areas of the country also express higher levels of tolerance in this respect.

Hindus who are more religiously observant tend to be somewhat less willing to accept a Muslim or a Christian in their neighborhoods. Among those who say religion is very important in their lives, 56% say they would be willing to accept a Muslim as a neighbor, compared with 62% of those who consider religion less important to them.

Politically, Hindus who voted for the BJP in the 2019 elections tend to be less willing to accept some religious minorities in their village or residential area. About half of Hindus who voted for the BJP say they would be willing to accept a Muslim (51%) or a Christian (53%) as neighbors, compared with higher shares of those who voted for other parties (64% and 67%, respectively). But there is little difference by partisanship among Hindus when it comes to whether they would be willing to accept a Sikh, Buddhist or Jain as a neighbor.

Hindus also vary regionally in their attitudes on accepting religious minorities. Hindus in the Central region tend to be less willing to accept a Muslim (46%) or a Christian (45%) as a neighbor. Meanwhile, far larger shares of Hindus in the South say they would be willing to have Muslims (75%) or Christians (77%) living nearby.

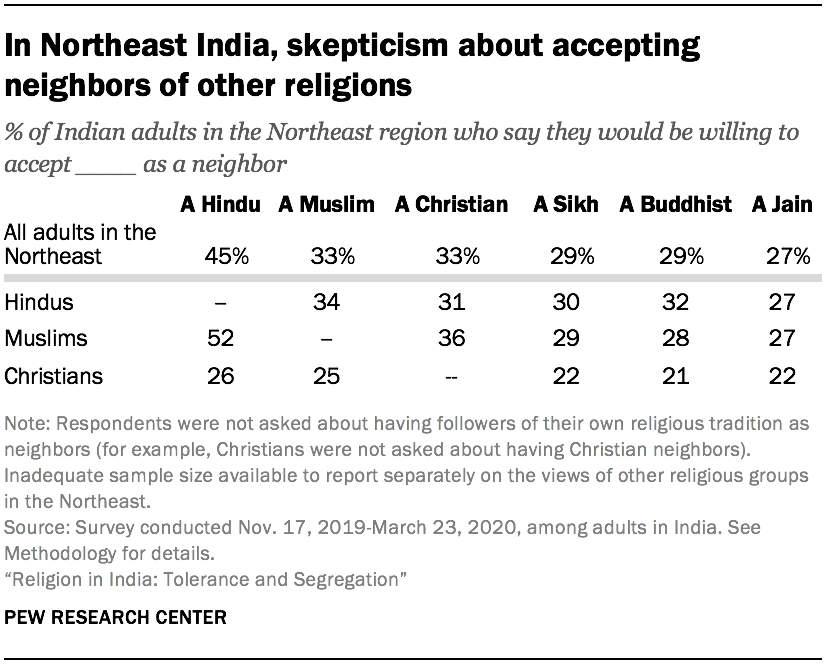

In general, Indians in the remote Northeastern region are less likely than people elsewhere to express a willingness to accept members of other faiths. For instance, about one-in-three Hindus in Northeastern India say they would be willing to live near a Muslim (34%) or a Christian (31%), compared with majorities of Hindus nationally who say they would be willing to live near a member of either religious group. Among Muslims and Christians in the region, about half or fewer express willingness to live near a Hindu, or near each other. For example, roughly one-third (36%) of Muslims in the Northeast say they would accept a Christian neighbor, and 25% of Christians would accept a Muslim neighbor.

In general, Indians in the remote Northeastern region are less likely than people elsewhere to express a willingness to accept members of other faiths. For instance, about one-in-three Hindus in Northeastern India say they would be willing to live near a Muslim (34%) or a Christian (31%), compared with majorities of Hindus nationally who say they would be willing to live near a member of either religious group. Among Muslims and Christians in the region, about half or fewer express willingness to live near a Hindu, or near each other. For example, roughly one-third (36%) of Muslims in the Northeast say they would accept a Christian neighbor, and 25% of Christians would accept a Muslim neighbor.

Notable shares in the Northeast also report that they “don’t know” or otherwise refused to answer the question, possibly due to unfamiliarity with some groups. For example, roughly one-in-five or more Muslims and Christians opt out of answering the question about Sikhs and Jains – groups that make up only a tiny share of the region’s population. For more on religious divisions in Northeastern India, see Chapter 1.

Indians generally marry within same religion

Very few Indians say they are married to someone who currently follows a different religion than their own. Indeed, nearly all married people (99%) report that their spouse shares their religion. This includes nearly universal shares of Hindus (99%), Muslims (98%), Christians (95%), Sikhs and Buddhists (97% each). (The survey did not include enough interviews with married Jains to report on the religion of their spouses.)

Very few Indians say they are married to someone who currently follows a different religion than their own. Indeed, nearly all married people (99%) report that their spouse shares their religion. This includes nearly universal shares of Hindus (99%), Muslims (98%), Christians (95%), Sikhs and Buddhists (97% each). (The survey did not include enough interviews with married Jains to report on the religion of their spouses.)

The survey also asked respondents whether their spouse was raised in their current religion, or whether their spouse was raised in a different religion and converted. Overall, the vast majority of people say their spouse currently has the same religion in which he or she was raised. Less than 1% of all Indian marriages are with spouses who were raised in a different religion (but may have since converted). (For a more detailed discussion of religious conversion, see “Religious conversion in India” in the report overview.)

Most Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs and Jains strongly support stopping interreligious marriage

Not only are interreligious marriages rare in India, but in recent years, some couples marrying outside their communities have experienced severe consequences, including being ostracized and even killed by family members.

Not only are interreligious marriages rare in India, but in recent years, some couples marrying outside their communities have experienced severe consequences, including being ostracized and even killed by family members.

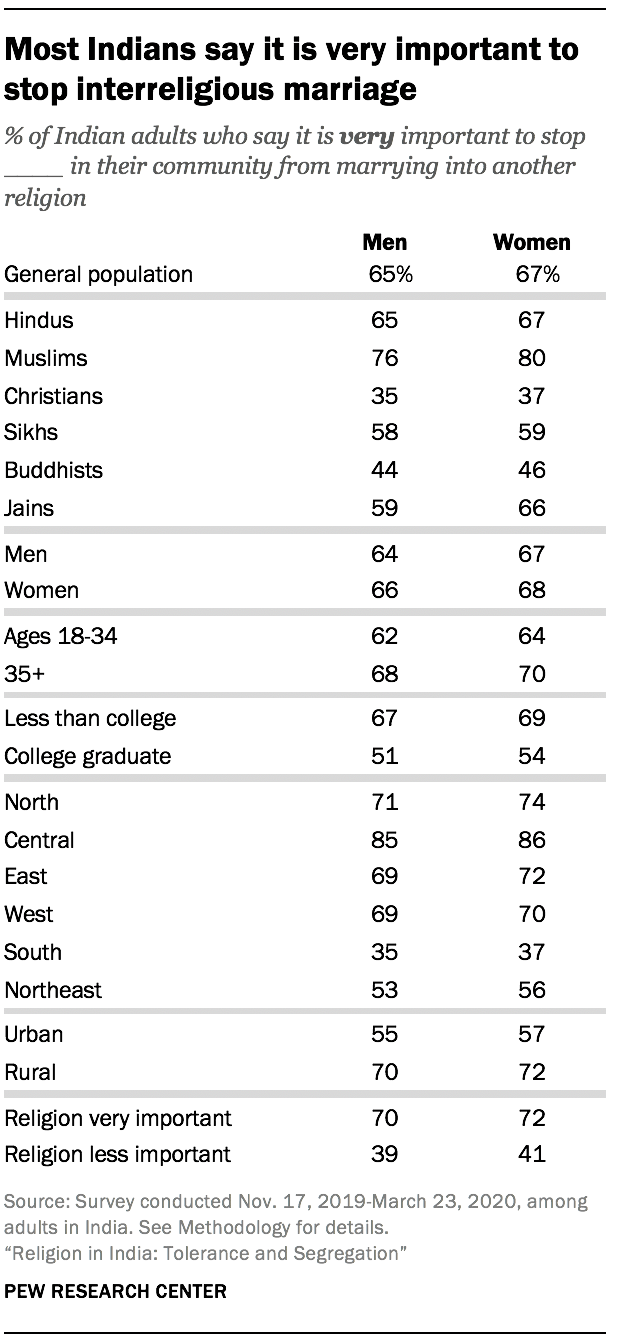

The survey asked Indians how important it is to stop men and women in their community from marrying into another religion. Overwhelming shares of Indians say it is at least “somewhat” important to stop people from entering into interreligious marriages, and most say it is “very” important to stop such marriages. (For an analysis of attitudes on stopping inter-caste marriage, see Chapter 4.)

The Indian public prioritizes stopping the interreligious marriage of women and men at nearly equal rates. About two-thirds of Indians (65%) say it is very important to stop men from marrying into another religion, while roughly the same share (67%) say stopping interreligious marriage of women is a high priority.11

Most Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs and Jains say it is very important to stop men and women in their community from marrying outside their religion. But considerably fewer Christians and Buddhists feel this way. Among Christians, 37% say it is very important to stop the interreligious marriage of women, and 35% say the same about men. Among Buddhists, 46% say stopping the interreligious marriage of women is a high priority, and 44% say this for men.

Highly religious Indians are especially likely to prioritize stopping interreligious marriage. For example, among adults who say religion is very important in their lives, a majority (70%) give high priority to stopping the interreligious marriage of men, compared with 39% of those who say religion is less important to them.

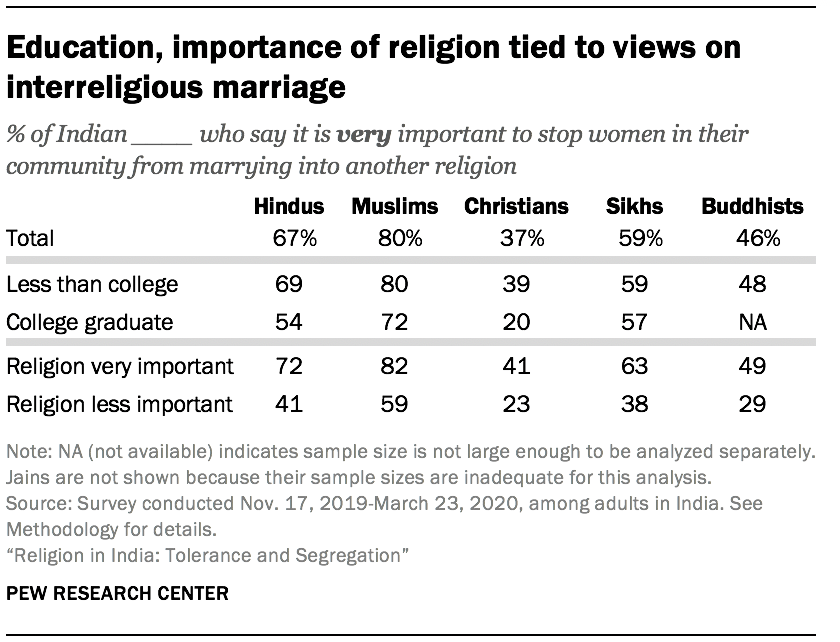

Nearly all religious groups show this gap in opinion. Among Muslims, for example, 82% of those who consider religion to be very important in their lives say stopping women in their community from marrying into other religions is very important, compared with 59% of Muslims for whom religion is less important.

Nearly all religious groups show this gap in opinion. Among Muslims, for example, 82% of those who consider religion to be very important in their lives say stopping women in their community from marrying into other religions is very important, compared with 59% of Muslims for whom religion is less important.

In addition, Indians with lower levels of education are much more likely than college-educated Indians to prioritize stopping interreligious marriage. Among those who do not have a college education, roughly two-thirds (69%) say stopping the interreligious marriage of women is very important, compared with 54% among those with a college degree. This pattern is consistent across most religious groups.

Men and women are generally about equally likely to favor preventing people of both sexes from marrying outside of their religion. For example, 67% of men say it is very important to stop women in their community from marrying outside of their religion, while 68% of women express the same position.

However, attitudes about religious intermarriage vary greatly depending on where people live in the country. Rural Indians are more likely than those who live in urban environments to say it is very important to stop both men and women from marrying outside of their religion.

And Indians who live in the Central region of the country are more inclined than people in other regions to say it is very important to stop people from marrying outside of their religion. Among Hindus in the Central region, for instance, 82% say stopping the interreligious marriage of Hindu women is very important, compared with 67% of Hindus nationally. Among Muslims in the region, nearly all (96%) see it as crucial to stop Muslim women from marrying outside the faith, versus 80% of Muslims nationally.

Southerners are much less likely to prioritize stopping interreligious marriage. Among both Hindus and Muslims, fewer people in the South than in other regions say it is very important to stop the interreligious marriage of men or women in their community.

Southerners are much less likely to prioritize stopping interreligious marriage. Among both Hindus and Muslims, fewer people in the South than in other regions say it is very important to stop the interreligious marriage of men or women in their community.

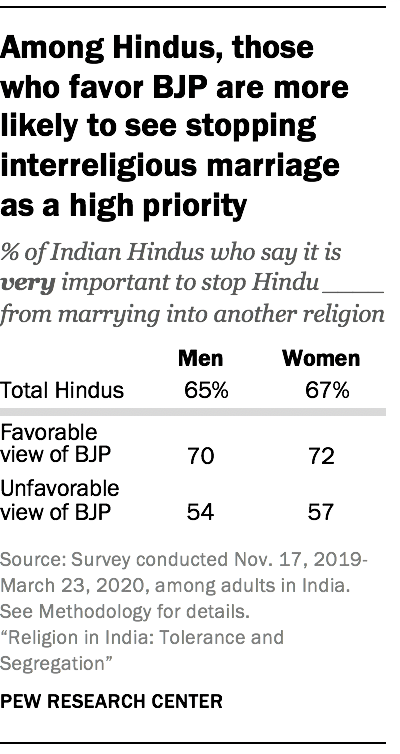

Among Hindus, those who have a favorable view of the BJP are more likely than those who see the BJP unfavorably to prioritize stopping the interreligious marriage of men or women. A large majority (70%) of those who have a favorable view of the BJP say stopping Hindu men from intermarrying is very important, compared with just over half of those who have an unfavorable view of the ruling party (54%). Hindus show a similar gap in opinion by partisanship when it comes to interreligious marriage of Hindu women.

An index of religious segregation in India

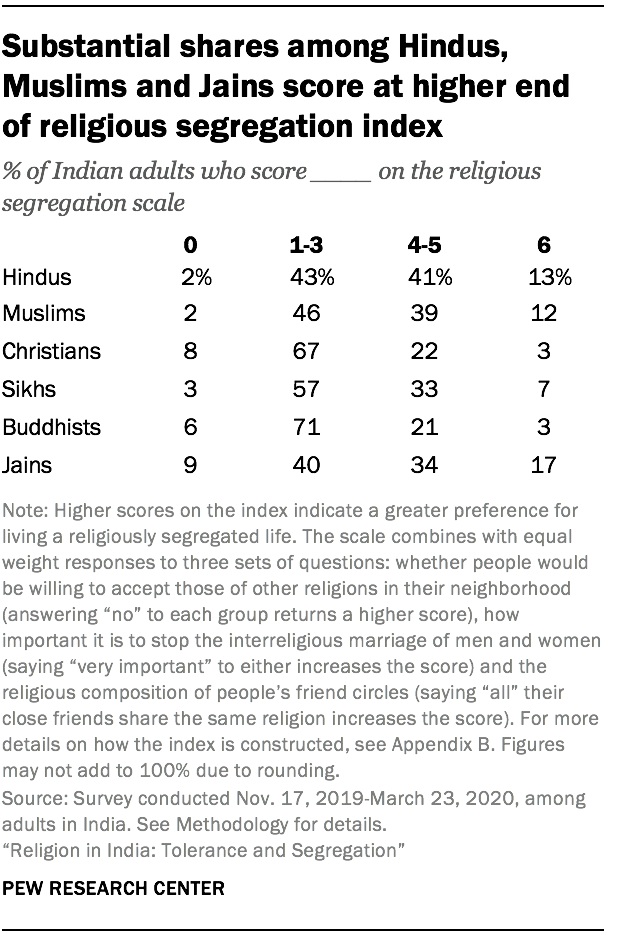

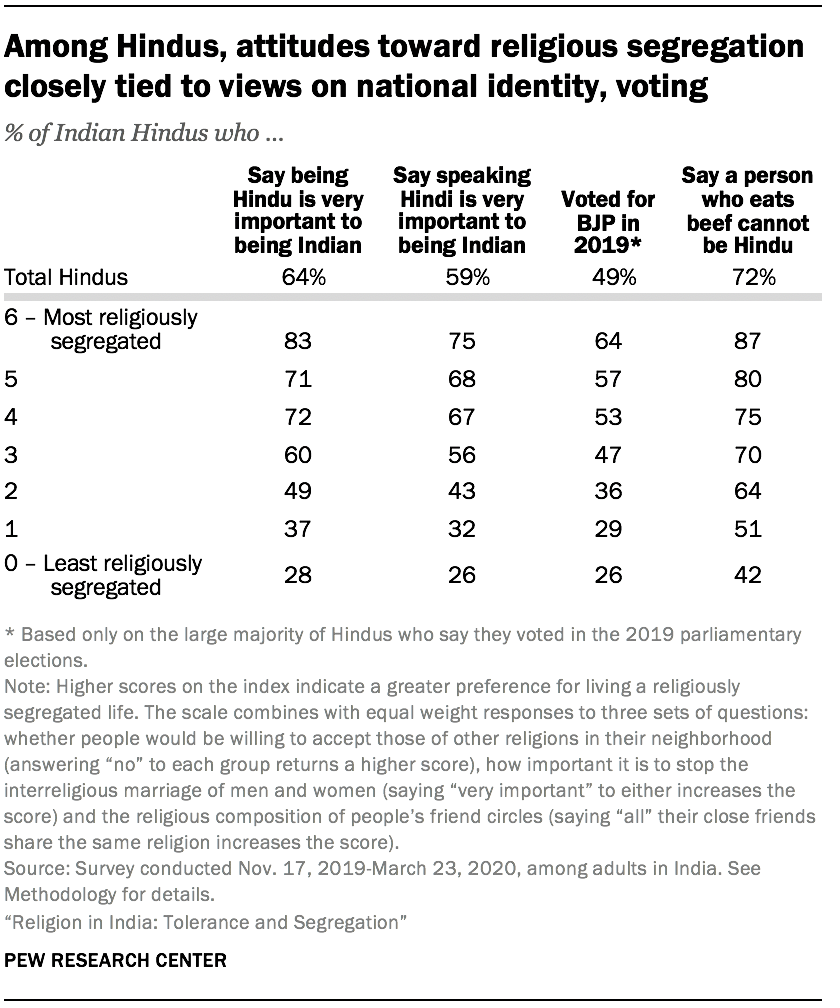

How people form friendship circles, the importance they place on stopping interreligious marriages and their views on who they are willing to accept in their neighborhood can be combined into an index of religious segregation that ranges from 0 to 6.

How people form friendship circles, the importance they place on stopping interreligious marriages and their views on who they are willing to accept in their neighborhood can be combined into an index of religious segregation that ranges from 0 to 6.

The higher the score on the scale, the more the respondent prefers religious segregation. For instance, people who say all their friends belong to the same religion, that they consider it very important to stop interreligious marriage, and that they would object to having people of every other religion as a neighbor would score the highest on the scale (6).

Those who have a religiously mixed friend circle, don’t think it is important to stop interreligious marriage and don’t object to having people of any other religion as neighbors would score at the lowest level (0). In between is a spectrum of preferences about the extent to which people prefer to live religiously segregated lives. (For more details on how the scale is constructed, see Appendix B.)

Few Indians score at the extreme ends of the scale, either scoring 0 (the lowest level of preference for religious segregation) or scoring 6 (the highest level of preference for religious segregation). For example, just 2% of Hindus score 0 and 13% score 6, which is comparable to the shares of Muslims who receive these scores on the index.

But half or more of Hindus (55%), Muslims (51%) and Jains (51%) rank toward the high end of the religious segregation scale, with a score of 4 or higher. Christians, Buddhists and Sikhs, meanwhile, tend to score lower, with majorities among all three groups at 3 or below.

Among Hindus, attitudes toward religious segregation are highly correlated with their views on religious and national identity. As Hindus’ score on the religious segregation index rises, so does their likelihood of saying it is very important to be Hindu to be “truly” Indian. And those who prefer to live more segregated lives also are more likely to say that it is very important to be able to speak Hindi to be truly Indian, as well as that a person who eats beef cannot be Hindu.

Among Hindus, attitudes toward religious segregation are highly correlated with their views on religious and national identity. As Hindus’ score on the religious segregation index rises, so does their likelihood of saying it is very important to be Hindu to be “truly” Indian. And those who prefer to live more segregated lives also are more likely to say that it is very important to be able to speak Hindi to be truly Indian, as well as that a person who eats beef cannot be Hindu.

Hindus who score high on the scale report having voted for the BJP at higher rates in the 2019 election, too.

Geographically, among Hindus, the Central region has the highest concentration of people who score a full 6 on the scale (23%). By comparison, just 4% of Hindus in the South score at the top of the scale.