This is the 12th in a series of annual reports by Pew Research Center analyzing the extent to which governments and societies around the world impinge on religious beliefs and practices. The studies are part of the Pew-Templeton Global Religious Futures project, which analyzes religious change and its impact on societies around the world.

To measure global restrictions on religion in 2019 – the most recent year for which data is available – the study rates 198 countries and territories by their levels of government restrictions on religion and social hostilities involving religion. The new study is based on the same 10-point indexes used in the previous studies.

- The Government Restrictions Index (GRI) measures government laws, policies and actions that restrict religious beliefs and practices. The GRI comprises 20 measures of restrictions, including efforts by government to ban particular faiths, prohibit conversion, limit preaching or give preferential treatment to one or more religious groups.

- The Social Hostilities Index (SHI) measures acts of religious hostility by private individuals, organizations or groups in society. This includes religion-related armed conflict or terrorism, mob or sectarian violence, harassment over attire for religious reasons and other forms of religion-related intimidation or abuse. The SHI includes 13 measures of social hostilities.

To track these indicators of government restrictions and social hostilities, researchers combed through more than a dozen publicly available, widely cited sources of information, including the U.S. Department of State’s annual reports on international religious freedom and annual reports from the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom, as well as reports and databases from a variety of European and United Nations bodies and several independent, nongovernmental organizations. (See Methodology for more details on sources used in the study.)

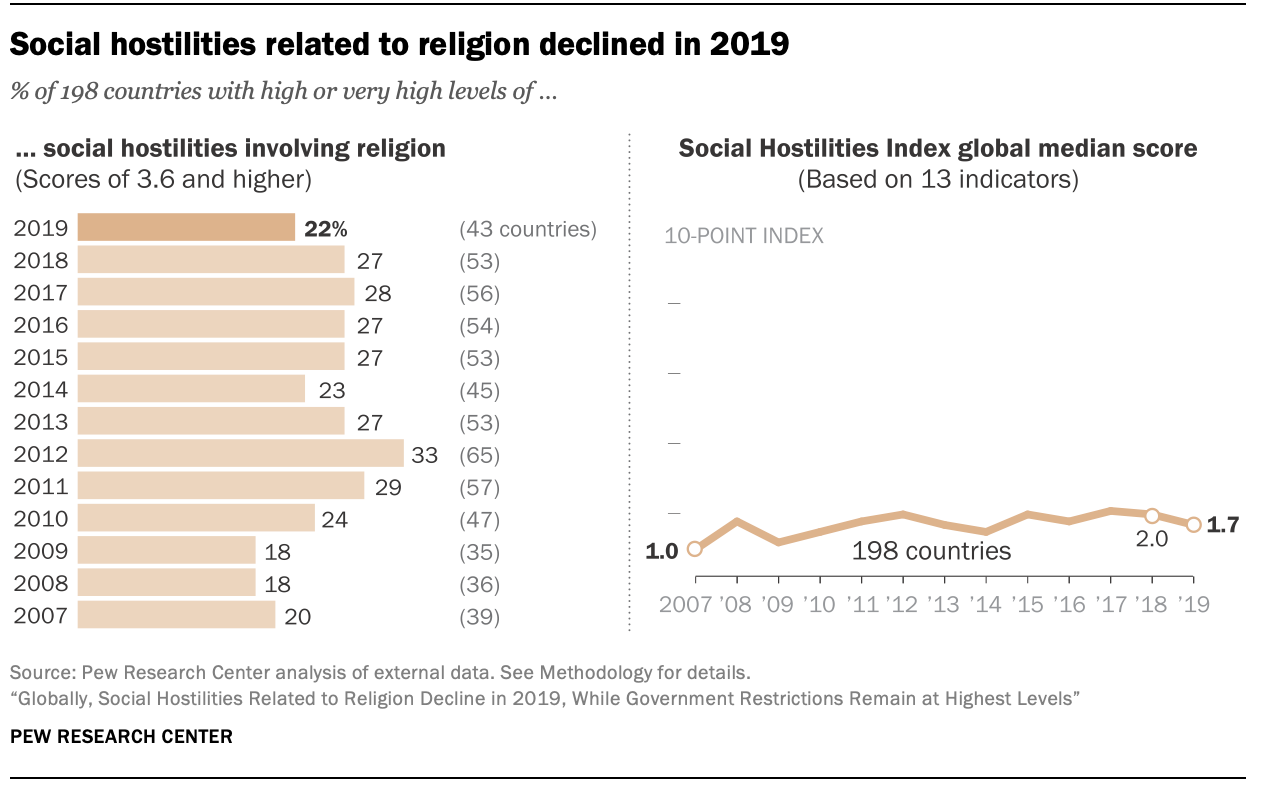

Social hostilities involving religion, including violence and harassment against religious groups by private individuals and groups, declined in 2019, according to Pew Research Center’s 12th annual study of global restrictions on religion, which examines 198 countries and territories.

In 2019 – the most recent year for which data is available, covering a period before the disruptions accompanying the coronavirus pandemic – 43 countries (22% of all those included in the study) had “high” or “very high” levels of social hostilities. That is down from 53 countries (27%) in 2018, and from a peak of 65 countries (33%) in 2012. These figures have fluctuated since the study began in 2007, but the number of countries with at least “high” levels of social hostilities related to religion is now the lowest since 2009.

Another way of looking at the data is by examining scores on the Social Hostilities Index (SHI), a 10-point scale based on 13 indicators of social hostilities involving religion. The global median score declined from 2.0 in 2018 to 1.7 in 2019, reaching its lowest level since 2014.

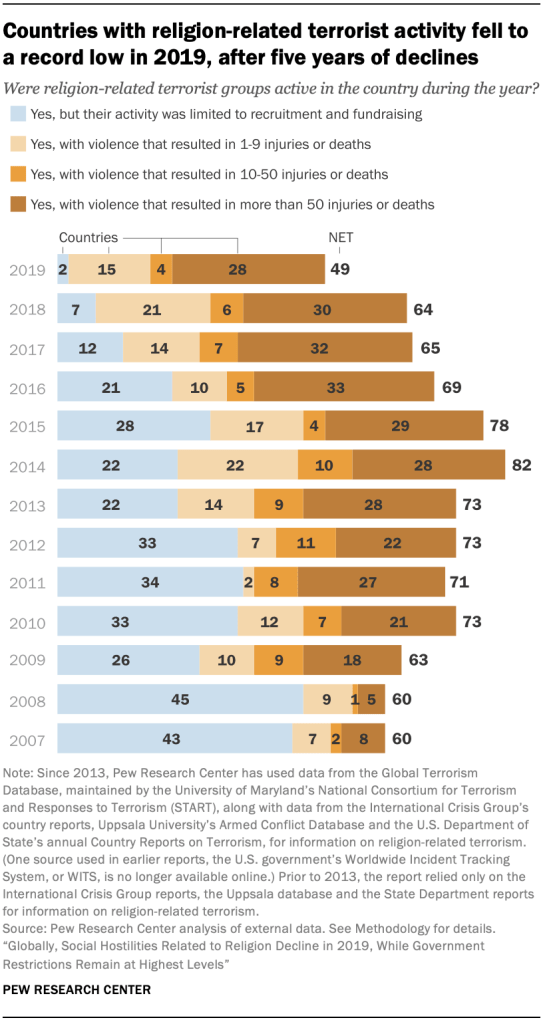

A drop in the number of countries experiencing religion-related terrorism (including deaths, physical abuse, displacement, detentions, destruction of property, and fundraising and recruitment by terrorist groups) is among the factors behind the decrease in social hostilities. In 2019, 49 countries experienced at least one of these types of religion-related terrorism, a record low for the study. That was down from 64 countries in 2018, and from a record high of 82 countries in 2014. The decline from 2018 occurred in four of the five regions analyzed: the Americas, the Asia-Pacific region, Europe and the Middle East-North Africa region. Only in sub-Saharan Africa did the number of countries with religion-related terrorism remain stable in 2019.

There also were fewer countries where religion-related terrorism led to deaths or injuries. In 2019, 47 countries had at least one casualty due to religion-related terrorism, down from 57 countries in 2018. In Morocco, for example, two Scandinavian hikers were murdered in 2018 by perpetrators who pledged allegiance to the Islamic State group (also known as ISIS, ISIL and Daesh), a militant Islamist organization; in 2019, no casualties from religion-related terrorism were reported in Morocco by the sources used in this study.1

The decline echoes a broader pattern recorded around the world in recent years. According to the Global Terrorism Database, which tracks a wide variety of terrorist incidents regardless of whether they are related to religion and is used as a source for this study, 2019 was “the fifth consecutive year of declining global terrorism” since a peak in 2014.2

That year, 2014, had many incidents of terrorist activity by the armed group ISIS and its affiliates, and by the militant Islamist group Boko Haram. ISIS formally established itself in Syria and Iraq in 2014 and engaged in a series of hostile acts – including mass executions, forced displacement of people, and the abduction and sexual abuse of thousands of women and children – against religious minorities and those viewed as opposing their group’s interpretation of Islam.3 ISIS also successfully recruited foreigners to join the fighting in Iraq and Syria and inspired affiliate groups and “lone offender” attacks globally.4 And Boko Haram kidnapped more than 250 schoolgirls, mainly Christians, from a school in Chibok, Nigeria, drawing international attention that year.5

Among the reasons for the decline in the study’s terrorism measures is that ISIS subsequently lost control of a large swath of territory in Iraq and Syria. In 2019, the Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS declared that the militant group had been territorially defeated. And the number of violent attacks perpetrated by the group declined in Iraq in 2019, according to the Global Terrorism Database.

Still, ISIS’s multinational network of organizations remained active. Groups pledging allegiance to ISIS carried out bombings in Sri Lanka on Easter Sunday, 2019, killing more than 250 people and injuring approximately 500 others at churches and hotels. Another exception to this overall decline in terrorism in 2019 was Afghanistan, where the number of terrorist incidents – particularly attacks carried out by the Taliban – increased amid peace talks between the group and the United States, according to the Global Terrorism Database.6

Beyond terrorism, other measures of religion-related social hostilities around the world also declined in 2019. For example, there were fewer countries with reports of mob violence related to religion (down from 41 countries in 2018 to 34 in 2019), hostilities over proselytizing (from 35 in 2018 to 28 in 2019), organized groups using force or coercion in an attempt to dominate public life with their perspectives on religion (104 to 94 countries), and individuals using violence or the threat of violence to enforce religious norms (85 to 74 countries). (See Appendix D for full results.)7

In Bolivia, for example, Protestant missionaries and pastors had been expelled in 2018 from rural areas where Indigenous spiritual beliefs are practiced, but no such expulsions were reported in 2019.8 And in Egypt, where social hostilities fell from “very high” to “high” in 2019, anti-Christian attacks (such as those against the Coptic Christian minority) and violence by Islamist groups declined, according to the U.S. Commission on International Religious Freedom (USCIRF). Although violence toward Christians continued in the country, there were fewer abductions and displacements reported in 2019.9

Looking at overall social hostilities involving religion by region, the median scores on the Social Hostilities Index (SHI) fell in 2019 in the Asia-Pacific region, Europe and sub-Saharan Africa. Levels of social hostilities remained stable and relatively high in the Middle East-North Africa region, where more than half of countries (55%) continued to have “high” or “very high” levels of social hostilities. They remained steady in the Americas, where social hostilities involving religion are rare compared with the rest of the world. See Chapter 3 for details.

Government restrictions involving religion stayed at the highest level since the study began

In addition to looking at social hostilities relating to religion, this annual study also examines government restrictions on religion – including official laws, policies and actions that impinge on religious beliefs and practices – in 198 countries and territories.

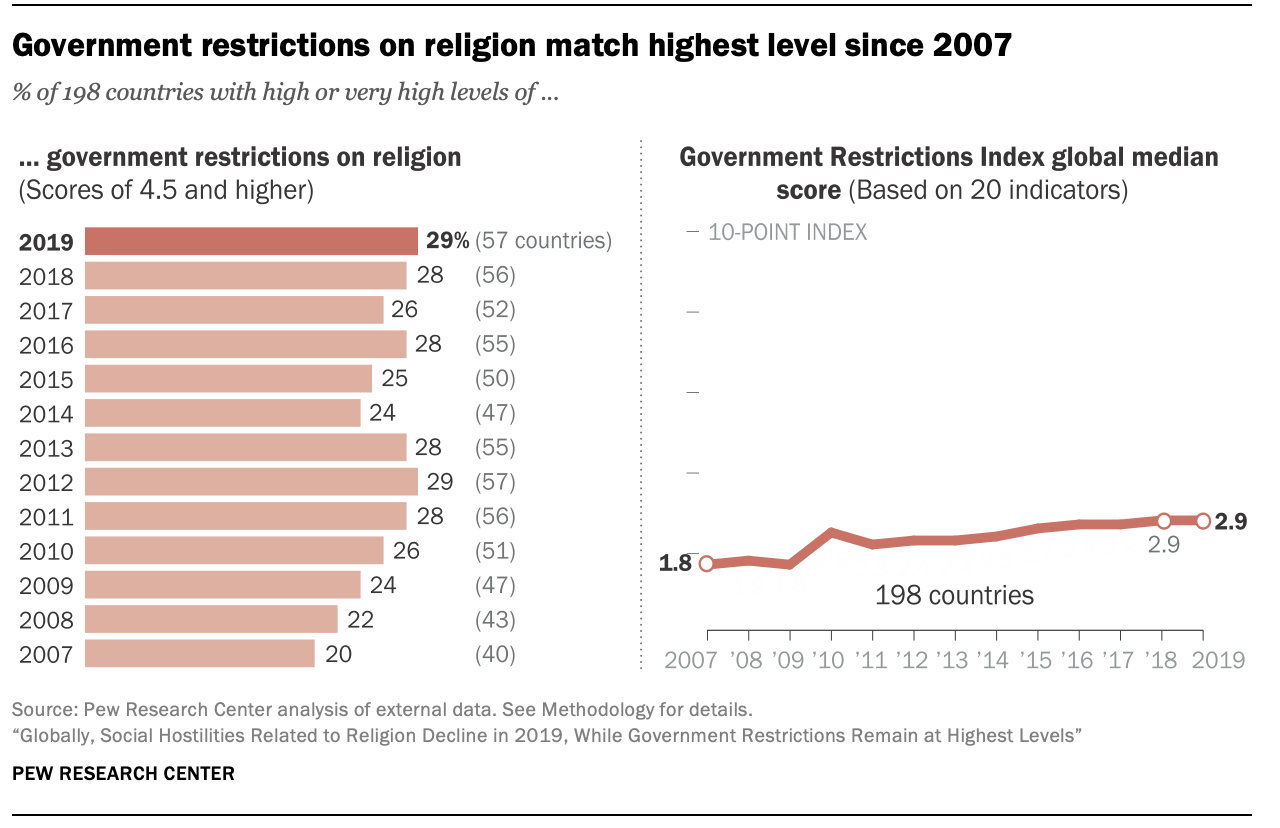

The analysis shows that government restrictions involving religion, which in 2018 had reached the highest point since the start of the study, remained at a similar level in 2019. The global median score on the Government Restrictions Index (GRI), a 10-point index based on 20 indicators, held steady at 2.9. This score has risen markedly since 2007, the first year of the study, when it was 1.8.

The total number of countries with “high” or “very high” levels of government restrictions rose in 2019 to 57 (29% of all countries in the study). This is up one country from 2018 and matches the study’s highest mark, from 2012.

As has been the case in all previous years studied, most countries with “high” or “very high” levels of government restrictions in 2019 were either in the Asia-Pacific region (25 of the 50 countries in that region) or in the Middle East-North Africa region (19 of 20 countries).

Looking at government restrictions and social hostilities together, 75 countries (38% of those included in the study) had “high” or “very high” levels of overall restrictions on religion in 2019, down from 80 countries (40%) in 2018.

For full results, see Appendix E.

Government harassment of religious groups and interference in worship increased

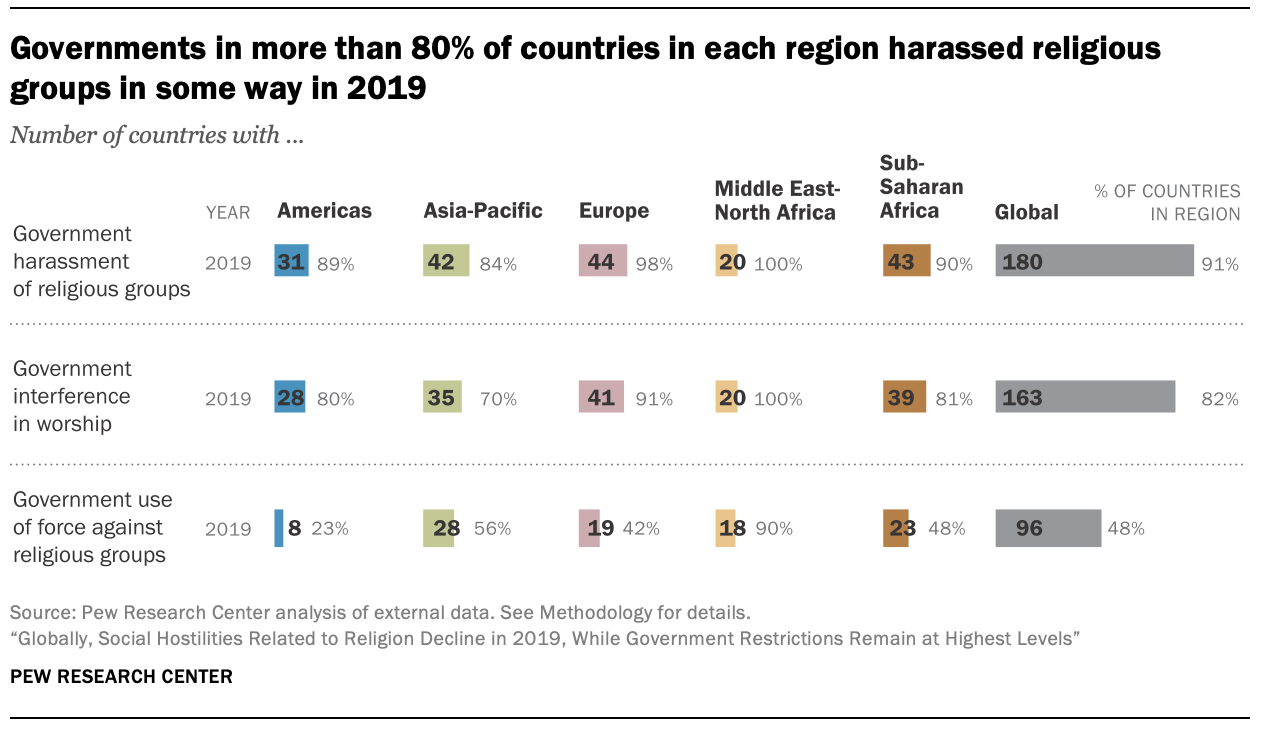

Two specific measures of government restrictions on religion increased globally in 2019: government harassment against religious groups and government interference in worship. More countries had at least one reported incident of government harassment or interference in worship in 2019 than in any other year since the study began in 2007.

While scores for these two measures of government restrictions increased in 2019, the scores for some other measures that make up the Government Restrictions Index decreased, which is why the global median score on the GRI remained stable. For example, fewer countries had limits on proselytizing and on foreign missionaries, and there were fewer reports of countries denouncing religious groups as “cults” or “sects.”

Definition: Government harassment of religious groups

Government harassment of religious groups takes place when officials at any level of government (e.g., national, provincial or municipal) target a religious group or person due to their religious identity, beliefs or practices. This may range from physical coercion to verbal statements singling out a religious group or individual with the intent of making their religious practice (or some other aspect of their lives) more difficult. For example, negative public comments by government officials about religions constitute harassment, as do government policies that target particular religious groups.

In total, 180 countries – 91% of all countries in the study – had at least one instance, at some level, of government harassment against religious groups, compared with 175 countries in 2018. In this study, harassment against religious groups can range from verbal intimidation to physical violence motivated at least in part by the target’s religious identity.

Governments in more than 80% of the countries in each of the study’s five regions harassed religious groups in some way, including all 20 countries in the Middle East-North Africa region and 44 of 45 in Europe (98% of countries in the region). In sub-Saharan Africa, 90% of the region’s 48 countries had such incidents, followed by 89% of the 35 countries in the Americas and 84% of countries in the Asia-Pacific region. In Tajikistan, for example, authorities in 2019 detained 17 Jehovah’s Witnesses – a group whose activities are banned in the country – for “possessing religious materials and participating in religious activities.”10 (For more information on government harassment of specific religious groups, see Chapter 2.)

Definition: Government interference in worship

Government interference in worship includes withholding permission for religious activities or prohibiting particular religious practices at any level of government. Religious practices are defined broadly. They range from worship activities (such as prayer, preaching or performing rituals) to wearing religious attire, adhering to grooming customs such as maintaining a beard, conscientious objection to military service, the use of certain substances (such as peyote) in worship and following ritual burial practices.

In 163 countries (82%), government authorities interfered in worship in ways such as prohibiting certain religious practices, withholding access to places of worship or denying permits for religious activities or buildings. In 2018, 156 countries interfered in worship in any of these ways.

All 20 countries in the Middle East-North Africa region also had occurrences of government interference in worship in 2019. And, as with the government harassment measure, Europe had the second-highest share of countries where governments interfered in worship (91%), followed by 81% of countries in sub-Saharan Africa, 80% in the Americas and 70% in the Asia-Pacific region. In Europe, for example, there were numerous restrictions on religious symbols and clothing, such as in Austria, where laws prohibit full-face coverings in public and ban headscarves for children under age 10 in elementary school.11 And in Slovenia, where animal slaughter without prior stunning is prohibited, Muslims and Jews are not allowed to slaughter animals according to halal and kosher dietary guidelines, respectively.12

While some level of government harassment of religious groups or interference in religious worship is common around the world, widespread physical harassment – i.e., government use of force against religious groups – is less common. In 96 of the 198 countries analyzed (48%), there was at least one report of governments using force against religious groups, including property damage, detention or arrests, ongoing displacement, physical abuse, and killings. In four of these countries – China, Myanmar (also called Burma), Sudan and Syria – there were more than 10,000 cases of government force against religious groups reported.

In China’s Xinjiang province, various sources have reported the detention of almost a million Uyghur Muslims and members of other religious and ethnic minority groups, as well as the separation of children from their families to curb the influence of religion in their homes (for more details, see Chapter 3).13 And in Syria, the government continued the “widespread and systematic use of unlawful killings” of perceived opponents (mostly Sunni Muslims) through torture, the destruction of civilian infrastructure, and the employment of chemical weapons, according to the U.S. State Department. The government also detained tens of thousands of Syrians, mainly Sunnis, without due process, according to numerous human rights organizations.14

In addition to ongoing restrictions on Rohingya Muslims in Myanmar, which have been discussed in previous years of this study, renewed fighting between the military and armed ethnic organizations in the country’s states of Kachin and northern Shan “deeply impacted” Christians, according to USCIRF. In 2019, thousands were displaced – including many Christians – in addition to more than 120,000 Rohingya who already had been internally displaced, and the military damaged over 300 churches.15

In Sudan, a nongovernmental organization estimated that in the country’s capital city, Khartoum, police arrested 40 women per day for violating Islamic dress standards.16 (The “public order law” that allowed such arrests was later repealed at the end of 2019, after the administration of President Omar al-Bashir was overthrown in April of that year.) During the year, authorities also used force against at least 500 worshippers at a mosque for participating in antigovernment protests that eventually led to the removal of the president.17

For more information on physical harassment involving government force against religious groups by region, see Chapter 2.

Religion-related restrictions online and use of technology to target groups

This 12th study of religious restrictions by Pew Research Center includes for the first time a measure assessing online restrictions by governments related to religion, as well as the governmental use of new or advanced technologies such as surveillance cameras, facial recognition technology or biometric data to restrict or surveil religious groups. In order to keep coding consistent with previous years, these new measures are not included when calculating GRI scores for countries.

In total, 28 countries and territories (14% of all 198 in the study) had some type of online governmental restriction in 2019 that was related to religion. Most were in either the Asia-Pacific region (15 countries) or in the Middle East-North Africa region (10 countries). For example, in Pakistan, where Islam is the official state religion, a cybercrimes court sentenced a Muslim man to five years in prison for posting “sacrilegious, blasphemous and derogatory” content online about an early Islamic leader with ties to the Prophet Muhammad.18 And in the United Arab Emirates, the country’s two main internet service providers, which are controlled by the government, blocked websites with information on Judaism, Christianity and atheism, as well as sites displaying testimonies from Muslim converts to Christianity.19

The study’s sources reported that 10 countries used technology to surveil religious groups in 2019, with three of them – China, Russia and Vietnam – citing security or counterterrorism efforts as a reason for such restrictions. In some countries, specific religious groups were targeted. In Armenia, for instance, members of the Baha’i faith alleged that authorities wiretapped the phones of a member of their community before charging him with facilitating illegal migration to the country.20

Meanwhile, Saudi Arabia’s Ministry of Islamic Affairs monitored some sermon content at mosques using data from a mobile phone app it launched in 2018.21 In Iran, a human rights group reported that authorities launched targeted cyberattacks against religious minorities, such as Sufi Muslims, to steal their private information.22 And in China, the state installed surveillance equipment in churches, mosques, a synagogue and other houses of worship; the government also used facial recognition technology to monitor and collect biometric data on Uyghur Muslims and other groups deemed to be potential threats. Authorities in Xinjiang also required Uyghurs to install software on their phones to monitor their calls and messages.23

The following sections of the report discuss other changes in restrictions on religion in 2019, including countries with the most extensive government restrictions and social hostilities involving religion, and the extent of changes in restrictions since 2018 (Chapter 1); additional details on harassment of specific religious groups and types of physical harassment by region (Chapter 2); and further analysis of restrictions on religion by region (Chapter 3), and in the world’s 25 most populous countries (Chapter 4).

Full results for all countries are available in Appendix E.